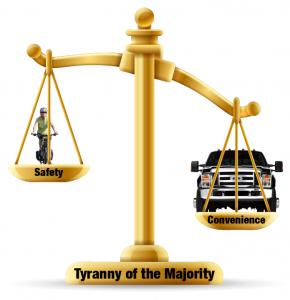

Bicyclists across the US, including a number in Florida 1 and California 2 have recently reported that they were harassed by police and ticketed for riding in the center of travel lanes that are too narrow to share safely side-by-side with cars and trucks. Florida and California have bicycle-specific laws 3 4 modeled after Uniform Vehicle Code § 11-1205(a), which requires bicyclists to ride as far right as “practicable” when traveling slower than other traffic. 5 Like the UVC version, the Florida and California bicycles-stay-right laws include an exception for lanes that are too narrow for riding side-by-side with a motor vehicle to be safe (in addition to many other exceptions such as on-street parking and surface hazards). Unfortunately, many police ignore the exceptions and use the stay-right requirement to harass or ticket cyclists whenever other traffic must slow for them.

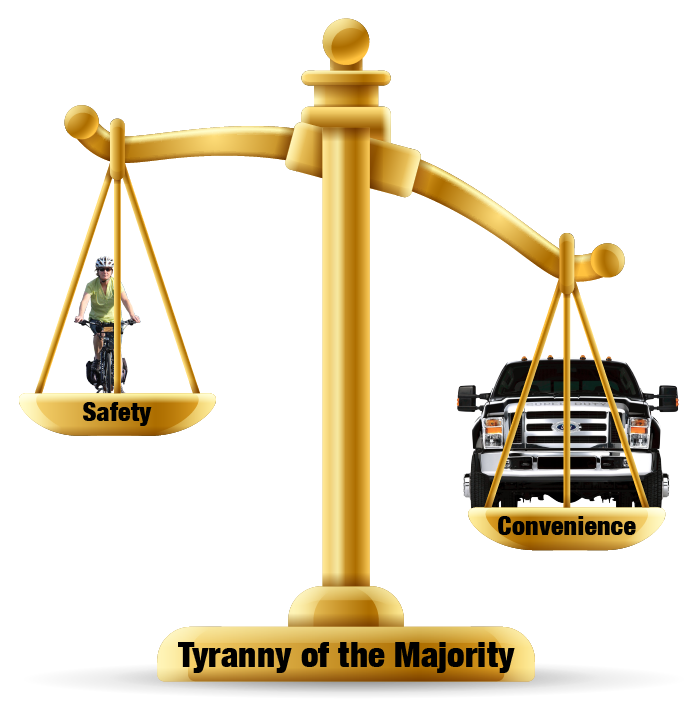

When so many bicyclists operating according to best practices are cited for violation of the law, we must conclude that there is something wrong with the law.

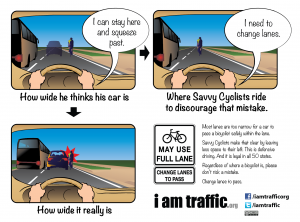

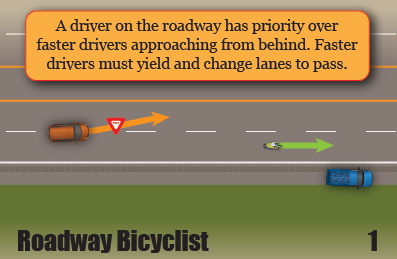

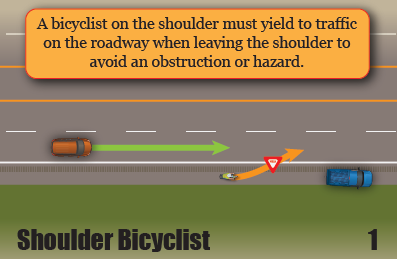

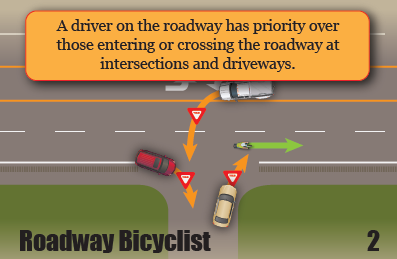

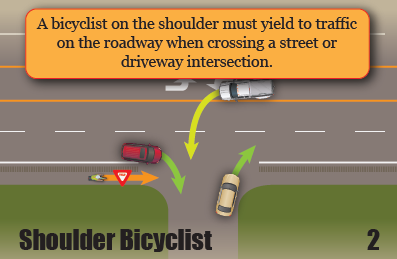

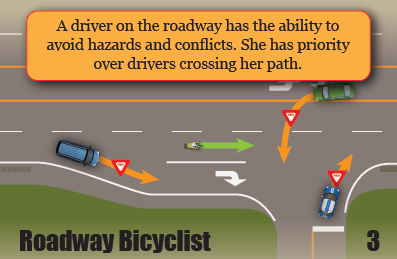

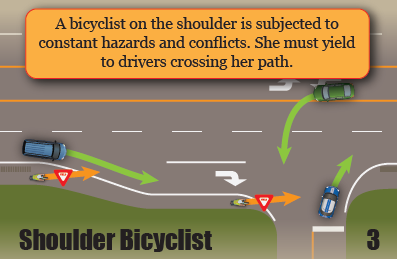

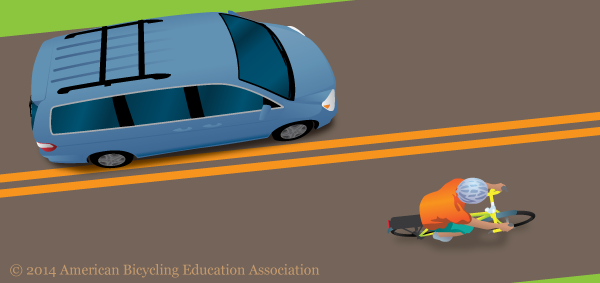

When so many bicyclists operating according to best practices 6 are cited for violation of the law, we must conclude that there is something wrong with the law. One observation is that since most travel lanes are 10 to 12 feet wide – too narrow for safe side-by-side sharing by a typical SUV, much less a truck or bus 7 – the law has the general rule (stay right) and the exception (narrow conditions) completely backward. Police officers assume that the law wouldn’t be written the way it is unless bicyclists should stay to the right edge of the lane most of the time, and so they send lane-controlling bicyclists to court again and again, only to have such cases dismissed. 8 This poorly conceived and written law generates needless conflict between police departments and the bicycling community. A somewhat better bicycle-specific law would declare bicyclists’ right to a full marked travel lane as a general rule, and define the exceptional circumstances where same-lane passing may be allowed. (Multiple criteria must be met: An especially wide lane allowing abundant passing distance given the vehicle width, a location away from intersections, safe conditions at the right edge of the lane given the bicyclists’ speed, and so forth.) The states of Colorado and Montana have each modified their bicycles-stay-right law with a step in this direction.

But what would happen instead if states did away with the bicycle-specific stay-right law entirely, as the NCUTLO Panel on Bicycle Laws recommended in 1975 9? Would traffic grind to a halt? No, but it would be harder for police to ticket bicyclists who exercise lane control for their own safety. We know this because six states – Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania – never adopted a bicycle-specific stay-to-the-right law. North Carolina has only a generic slow vehicle law, 10 similar to UVC 11-301(b):

UVC 11-301 – Drive on right side of roadways – exceptions …

(b) Upon all roadways any vehicle proceeding at less than the normal speed of traffic at the time and place and under the conditions then existing shall be driven in the right-hand lane then available for traffic, or as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway, except when overtaking and passing another vehicle proceeding in the same direction or when preparing for a left turn at an intersection or into a private road, alley, or driveway. The intent of this subsection is to facilitate the overtaking of slowly moving vehicles by faster moving vehicles. …

The driver of any vehicle traveling slowly can satisfy this law by using the right hand thru lane; only if there are no marked lanes is such a driver compelled to operate “as close as practicable” to the road edge.

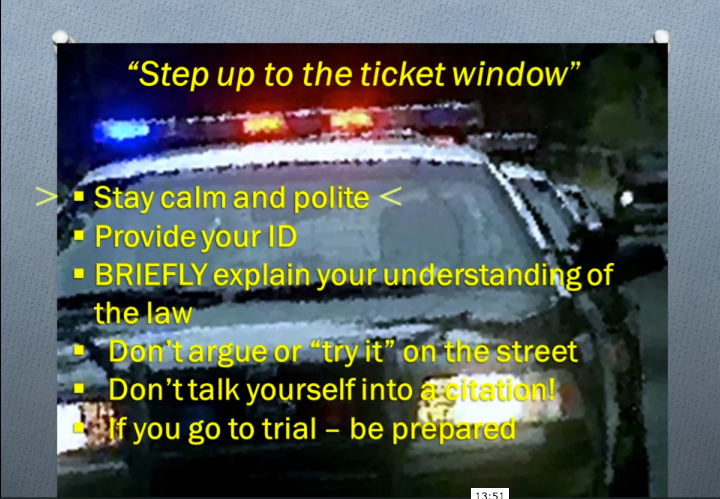

Having no discriminatory bicycle-specific stay-right law doesn’t make lawful cyclists immune to police harassment rooted in ignorance and bias. A lack of adequate police education about bicycling in North Carolina has resulted in many bicyclists (including myself) being pulled over by police who felt we shouldn’t be riding in the center of a narrow lane. The difference in North Carolina is that when the stopped bicyclists invite police to look up the statute, the officers usually recognize their error about the state law. The contrast between an unfair citation and a teachable moment is of great significance to the bicyclist. It’s possible that some bicyclist somewhere in North Carolina has paid a ticket for violating our state’s generic slow vehicle law, but our statewide advocacy organization isn’t aware of one, and we are vigilant.

Bicyclist advocates in North Carolina are actively engaging local police departments to promote better police relations and improved public safety, including education about best bicycling practices. When discussion of bicyclist positioning on the roadway comes up, we explain the technical issues of why it is often safer to ride in the center of the lane or control it by riding double file. This conversation with police is made much easier by the fact that North Carolina has no bicycle-specific stay right law. Question: “Don’t bicyclists legally need to stay to the right side of the lane?” Answer: “No, state law treats bicyclists the same as the driver of a slow moving tractor; they can occupy a travel lane. Next question?” Our state Driver Handbook underscores this point. “Bicyclists usually ride on the right side of the lane, but are entitled to use the full lane.” 11 North Carolina’s vehicle code clearly defines bicycles as vehicles and bicyclists as having the rights and duties of drivers of vehicles. Bicyclists don’t need a vehicle-specific law to telling them where to ride in a marked travel lane – or that they are allowed to occupy travel lanes in the first place – any more than motorcyclists do.

Do bicyclists in North Carolina ever control a wide travel lane under conditions where it creates an unreasonable delay for motorists, but with no real safety benefit? Yes, but such situations are very rare, firstly because so few lanes are truly wide enough for this to be safe, secondly because roads that carry substantial traffic will usually have an additional same-direction lane for passing, and thirdly because cyclists will usually move to the right as a courtesy when it will make a significant improvement for others. Contrary to what some people may think, bicyclists are human beings who typically care about other people, and some have written a good deal about this. 12 The rare cases where motorists experience significant delays from unnecessary control of wide lanes are too few and far between to warrant adopting a law that invites abuse from police and encourages unsafe edge riding.

Living without laws that punish bicyclists for being slower than motorcyclists and narrower than tractors has worked well in North Carolina. Bicyclist advocates in other states would do well to pursue the same full driver rights.

Notes:

- Guy Hackett, Ryan Scofield: “Cyclist fights ticket for using full lane, and wins” ↩

- David Kramer (6/29/2014), Scott Golper (7/6/2014), Greg Liebert (11/10/2013) ↩

- 316.2065(5)(a) Any person operating a bicycle upon a roadway at less than the normal speed of traffic at the time and place and under the conditions then existing shall ride in the lane marked for bicycle use or, if no lane is marked for bicycle use, as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway except under any of the following situations:

1. When overtaking and passing another bicycle or vehicle proceeding in the same direction.2. When preparing for a left turn at an intersection or into a private road or driveway.

3. When reasonably necessary to avoid any condition or potential conflict, including, but not limited to, a fixed or moving object, parked or moving vehicle, bicycle, pedestrian, animal, surface hazard, turn lane, or substandard-width lane, which makes it unsafe to continue along the right-hand curb or edge or within a bicycle lane. For the purposes of this subsection, a “substandard-width lane” is a lane that is too narrow for a bicycle and another vehicle to travel safely side by side within the lane. ↩

- 21202. (a) Any person operating a bicycle upon a roadway at a speed less than the normal speed of traffic moving in the same direction at that time shall ride as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway except under any of the following situations:

(1) When overtaking and passing another bicycle or vehicle proceeding in the same direction.

(2) When preparing for a left turn at an intersection or into a private road or driveway.

(3) When reasonably necessary to avoid conditions (including, but not limited to, fixed or moving objects, vehicles, bicycles, pedestrians, animals, surface hazards, or substandard width lanes) that make it unsafe to continue along the right-hand curb or edge, subject to the provisions of Section 21656. For purposes of this section, a “substandard width lane” is a lane that is too narrow for a bicycle and a vehicle to travel safely side by side within the lane.

(4) When approaching a place where a right turn is authorized.

(b) Any person operating a bicycle upon a roadway of a highway, which highway carries traffic in one direction only and has two or more marked traffic lanes, may ride as near the left-hand curb or edge of that roadway as practicable. ↩ - UVC 11-1205 Position on roadway

(a) Any person operating a bicycle or a moped upon a roadway at less than the normal speed of traffic at the time and place and under the conditions then existing shall ride as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway except under any of the following situations:- When overtaking and passing another bicycle or vehicle proceeding in the same direction.

- When preparing for a left turn at an intersection or into a private road or driveway.

- When reasonably necessary to avoid conditions including, but not limited to, fixed or moving objects, parked or moving vehicles, bicycles, pedestrians, animals, surface hazards, or substandard width lanes that make it unsafe to continue along the right-hand curb or edge. For purposes of this section, a “substandard width lane” is a lane that is too narrow for a bicycle and a vehicle to travel safely side by side within the lane.

- When riding in the right turn only lane.

(b) Any person operating a bicycle or a moped upon a one-way highway with two or more marked traffic lanes may ride as near the left-hand curb or edge of such roadway as practicable. ↩

- Cycling Savvy “FAQ: Why do you ride like that?” ↩

- Interactive Graphics: Lane Width and Space ↩

- “Cyclist fights ticket for using full lane, and wins” ↩

- In 1975, the NCUTLO Panel on Bicycle Laws wrote:

UVC § 11-1205(a) requires bicyclists to ride as close as practicable to the right hand side of the roadway. This provision is very unpopular with bicyclists for a number of reasons. It treats the bicyclist as a second class road user who does not really have the same rights enjoyed by other drivers but who is tolerated as long as he uses a bare minimum of roadway space at the side of the road. The provision is also frequently misunderstood by bicyclists, motorists, policemen and even, unfortunately, judges. The provision requires the bicyclist to be as close to the side of the road as is practicable, which we all understand to mean possible, safe and reasonable. But many people apparently don’t understand the significance of the word practicable, and read the law as requiring a constant position next to the curb. Even where the significance of the word practicable is recognized, the bicyclist is exposed to the danger of policemen and judges who may have a different idea about what is possible, safe and reasonable, and he is exposed to the very real danger of motorists who, because of their misconception of this law, will expect the bicyclist to stay next to the curb and will treat him with hostility if he moves away from that position.

The side of the road is a very dangerous place to ride. The bicyclist is not nearly as visible here as he is out in the center of a lane. Also there is reason to believe that motorists don’t respect a bicycle as a vehicle when it is hugging the side of the road. It is at the side of the road where all the dirt, broken glass, wire, hub caps, rusty mufflers, and other road debris collects, and it is hazardous to try to ride through this mess. Storm sewer grates are generally at the side of the road. The roadway is frequently less well maintained in this position. Also, in urban areas there is frequently a dangerous ridge where the roadway pavement meets the gutter, and the bicyclist must try to ride parallel with this ridge without hitting it. A bicyclist riding near the right edge of the roadway is also in substantially greater danger from vehicles cutting in front of him to turn right than is the bicyclist who rides out in the middle of the right lane.

https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B8yYlSlJo3DfbnVRVUhxVExLaDQ/edit ↩

- NC § 20-146(b): Upon all highways any vehicle proceeding at less than the legal maximum speed limit shall be driven in the right-hand lane then available for thru traffic, or as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the highway, except when overtaking and passing another vehicle proceeding in the same direction or when preparing for a left turn. ↩

- North Carolina Driver Handbook, Page 77 ↩

- What is a Courteous Cyclist? ↩

Right up front the League’s methodology for selecting and analyzing crashes has a built-in bias. The report states clearly that:

Right up front the League’s methodology for selecting and analyzing crashes has a built-in bias. The report states clearly that:

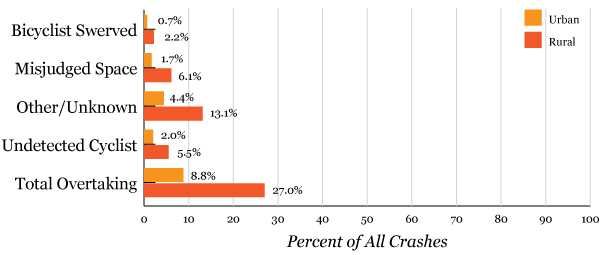

While the League report paid legitimate attention to unsafe and illegal motorist behaviors that led to deaths, such as intoxication, distraction and leaving the scene, it’s also a sad fact that many bicyclist deaths involve cyclists behaving similarly. But the League report was strangely silent on this. In North Carolina’s data 19% of fatalities involved an intoxicated cyclist. In metro Orlando it was 40% overall, two of the nine rural overtakings, and three of the six suburban overtakings involved intoxicated cyclists.

While the League report paid legitimate attention to unsafe and illegal motorist behaviors that led to deaths, such as intoxication, distraction and leaving the scene, it’s also a sad fact that many bicyclist deaths involve cyclists behaving similarly. But the League report was strangely silent on this. In North Carolina’s data 19% of fatalities involved an intoxicated cyclist. In metro Orlando it was 40% overall, two of the nine rural overtakings, and three of the six suburban overtakings involved intoxicated cyclists.