This story was originally published on CommuteOrlando, January 26, 2010. It has been updated here.

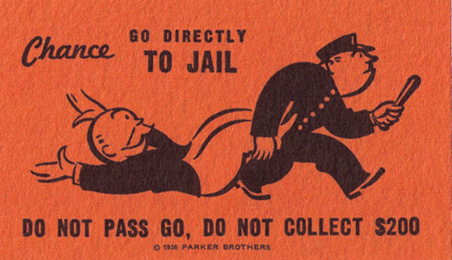

The Judge Mirandizes us as a group, then brings us forward one at a time to hear our plea, and the setting of a bond, etc. Those of us waiting are close enough to hear most of what is said.

When I approach his raised dais, he opens a folder, and then looks up in surprise. He says, “Are they serious? Operating a bicycle on the roadway?”

And as absurd as it sounds, my friend ChipSeal went back to jail that same night, arrested again on his way home from jail for operating on the roadway. What an incorrigible scofflaw! Read his story, beginning with While Minding My Own Business… I have great admiration for his gracious attitude toward those who detained him unfairly.

The right to travel by human power

ChipSeal’s case is a clear violation of his civil rights. The charge is unsupported by TX statute, and yet he was convicted of reckless driving and sentenced to time served (20 days).

When Eli Damon encountered an officer who didn’t want him on the roadway, he found himself charged with disorderly conduct. Eli maintains that he was calm and courteous in the encounter, but the officer was angered by his assertion that he was riding legally. The charge was prosecuted for four months before the prosecutor dropped it a week before the scheduled trial. You can read Eli’s story here.

In 2009, Bob Mionske covered the story of Tony Patrick, who was tasered and arrested for disorderly conduct in Chesapeake, OH for refusing an unlawful order to get off the road. His lawyer, Steve Magas, has more links to the story and the judge’s dismissal of charges here.

Being arrested for asserting your right to drive your bicycle on the road is an extreme violation of civil rights. But living under the specter of choosing between riding unsafely to avoid hassles and risking constant citations is also a violation of your right to travel by human power. In 2009, Fred U. experienced this in Port Orange, FL. The harassment ended when his lawyer got pretrial dismissals of all of his citations. Fred provided documentation for other cyclists who might face a similar predicament.

Cultural bias can be blinding

Nowhere is the bias more glaring than when an officer pulls a cyclist over for using one lane on an empty six-lane road on a Sunday morning. Then, during the stop the officer repeatedly asserts that the cyclist is failing to share the road by not riding at the far right of that lane. This might raise the question, with whom exactly is he failing to share the road? (See Red & Blue in the Rear View… Again?)

A few months ago, Mighk Wilson was pulled over for riding in one of three lanes on South Street. This is a one-way street, downtown, with a 30mph speed limit and plenty of traffic lights to prevent movement anywhere near that fast. Of course, when there are lots of motorists, traffic moves slower still. Agitated with Mighk’s knowledge of traffic law, the officer huffed that he was “one of those people who just doesn’t care about others.”

Bias denies basic human equity to its target. Bias is impervious to logic and reason. Bias is blind to its own absurdity, no matter how glaring. As much headway as we’re making with law enforcement, stubborn anti-cycling bias can still be encountered among the ranks of the most enlightened department.

These stories are infuriating to transportation cyclists in particular, but they cut even deeper for those who are car-free. When the cops are lying in wait for a cyclist who must pass through their jurisdiction, they are essentially violating that person’s right to use a public utility. By insisting, under threat of arrest, that a cyclist ride in a place not required by statute, these officers are abusing their authority.

Strategies for the chance encounter

Prompted by an Ask Geo email, I thought it might be a good idea to collect some wisdom on how to deal with uninformed police officers. I have not been pulled over or otherwise hassled by any of the many, many police officers who have passed me in my metro area travels. My interactions with them always consist of a friendly wave. But I know others who have been pulled over or ordered over the PA to ride far right. So I wondered, what’s the best way to conduct myself in a traffic stop? And how would/should I handle an officer giving me an unlawful order over his PA?

The unwarranted traffic stop

I think Richard Moeur’s story is exemplary in both his handling and its outcome. I got several good take-aways from it:

- Ask the officer’s intentions. Find out what he is requesting (ride on the sidewalk, ride on the edge of the road, ride on a different road).

- Resist the urge to discuss the law right away, and ask for a name and badge number.

- If the opportunity arises, be armed with a copy of the statutes.

- If the officer asks why you were riding where you were, present the pertinent talking points (know your talking points).

In my opinion, it’s better to not get a citation than to have to deal with one in court (even if you win). In the event that the officer does not respond favorably to your roadside defense, the best course may be finding a way to comply without compromising your safety, then deal with educating the officer via contact with the department.

The drive-by command

In the case of the cyclist who was told over the PA to get on the sidewalk, there is little recourse for dealing with the individual officer unless the officer stops. I’ve heard from several cyclists that deputies have told them over the PA to ride far right. This puts the cyclist in a predicament: comply and put her safety at risk (with no way to identify the officer); not comply and have an angry officer loop back around and pull her over; or flag the officer down and attempt to discuss it before he’s agitated by non-compliance.

There’s risk in that last option, too, depending on the officer’s attitude, as Brad Marcel in Tampa found out. When an officer ordered him to ride farther right in a narrow lane, he tried to flag her down to talk to her. She thought he’d flipped her off. He ended up receiving a citation and the officer has claimed that he was antagonistic (which he denies). In court the officer claimed he was impeding traffic (a statute which does not apply to non-motorized vehicles in Florida). He read the statute governing bicyclist lane position and explained that the lanes on road met the exemption of a “substandard” width lane because they are less than 14ft wide. The officer replied that no lanes in Tampa are 14ft wide, so that made no sense. The judge found him guilty.

So, I think Richard’s advice serves well here, too. If I could, I’d flag the officer down, ask him/her for clarification of the request and get a name and badge number. Depending on the officer’s demeanor, I might leave it at that and deal with unlawful demands higher up the chain of command.

Departmental bias

As far as I know, there are no systemic bias problems within any of the Orlando metro area police departments. As long as the source of the problem is an errant officer, it seems easiest to get the name and badge number and make nice till he goes away. Then I can deal with him through his supervisors. I also have the luxury of finding alternative routes and/or using my car until the situation is resolved.

Unfortunately, what ChipSeal and Eli are dealing with appears to be departmental. This was also the problem Fred encountered in Port Orange. He tried to go up the chain of command after the first encounter, to no avail. It took a swift pretrial dismissal of his citation to put a stop to his troubles. In the meantime, he faced harassment whenever he needed to travel through Port Orange to conduct business.

In December of 2009, Chipseal missed an appointment (after traveling a heck of a long way) because he was stopped three times for riding legally. We all thought that was over the top until he spent two nights in jail!

In one post, ChipSeal says

As it stands now, I am in under threat of arrest any time I travel, for slow vehicles like bicycles will, by their nature and in the strictest sense of the word, impede all other more powerful vehicles. How can I get to work? The grocer? Make appointments? Make any plans considering I could be jailed simply for using the public road? For leaving my driveway on a bicycle? Am I being subjected to a de-facto house arrest?

Eli’s saga is equally distressing. He’s been detained, had his bicycle confiscated and been arrested. His range of travel has been severely limited. He told me:

I have been on near virtual house arrest for the past several months. I am on bail because of the pending criminal charge so if I have another encounter, even with a different cop in a different town, before the case is resolved I could be put in jail until it is.

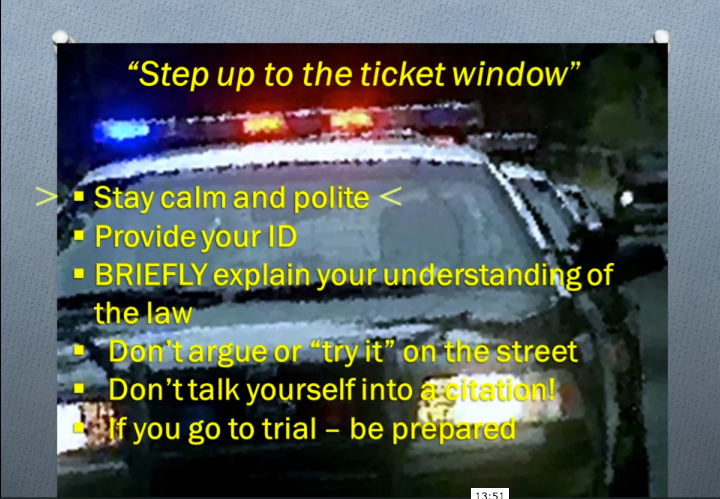

Of course, he’s learned a lot through his experience. Here’s some advice from him that I’ll keep in mind:

- Know the law (of course).

- If the officer asks for an explanation of your riding style, keep your answer concise (never too much information at once).

- Use formal, respectful language and don’t interrupt.

- “If the officer lets you go, do not ride away from the officer if you can help it. Let the officer leave first. You might have to walk to someplace that is a comfortable distance away but where you can still see the officer and wait awhile.”

- A suggestion Eli plans to use with potentially volatile officers in the future: ask, “Are you going to write me a ticket?” It could potentially end the encounter quickly and prevent arrest. A citation is certainly less inconvenient than going to jail.

- After the encounter, document everything that happened ASAP, contact appropriate authorities and assisting organizations. In Florida, contact George Martin.

- Again, get the name and badge number. Get it first, before you get distracted!

George Martin offers similar advice in his Ask Geo post today.

Correcting the cultural problem

Ultimately, these incidents are a manifestation of the bigger problem — what Steve Goodridge describes in America’s Taboo Against Bicycle Driving. The problem must be tackled from a number of directions. We are working very hard to build a mutually beneficial relationship with law enforcement and to create a program that will give them knowledge of the laws and help them understand how we protect ourselves on the road. But law enforcement officers are a part of our general culture. They’re people. They’re just as influenced as anyone else by the biases of the society in which they live.

The fundamental rule of the road is First Come, First Served (FCFS). The distorted rule of the Culture of Speed is All life yields to faster traffic. When the roads are governed by FCFS, pedestrians and bicycle drivers are people using public roads. When governed by the Culture of Speed, they are merely objects in the way.

As has been noted before, the Culture of Speed causes some police to enforce traffic flow vs safety. Worse, they often don’t even realize that their concepts of protecting safety are stealthy manifestations of the Great Reframing. Almost 100 years ago, traffic engineers began to manage the steady flow of automobiles at the expense of non-motorized users. The notion that speed differentials and lane changes cause safety problems resulting from the presence of a slow vehicle rather than the incompetent or aggressive behavior of faster drivers is a result of 100-year-old propaganda campaigns which removed pedestrians and bicyclists from the roads by dissociating safety from behavior. This is why most people, police officers included, don’t realize their ideas of safety are so badly skewed.

With this understanding, my friend ChipSeal’s graciousness is not only admirable, it is necessary to solve the problem. We have work to do. We need grace, understanding and cooperation. And we need those in law enforcement to be our allies.

Since the original publication of this post in 2010, Chipseal was charged and convicted of reckless driving (for what was essentially defensive driving). Eli has continued to face harassment from police departments in two Massachusetts towns. He has won his court cases and filed a lawsuit against one police department. In Florida, Fred U has faced repeated harassment from several police departments. Each time, he has won in court, but it has cost him hundreds of dollars in legal fees — to defend defensive driving.