It’s not Effective Cycling repackaged with a new name.

A common criticism of cyclist education is simply that “it doesn’t work.” Presented with such a statement, I suppose we first have to ask, “work at what?” Those making the claim seem to be saying it doesn’t work at getting more people to ride bikes. I don’t think many are claiming a trained cyclist is just as likely to crash as an untrained one.

Perhaps they may be right that it doesn’t get more people to ride bikes; but on the other hand I know individuals who have most certainly increased their cycling due to education. They have said so themselves. No doubt the “it doesn’t work” claim is based on a belief that few people will take a traffic cycling course.

This debate is at the core of how our society decides to promote cycling.

Do we take an ends-justify-the-means approach in which almost any strategy which encourages people to bike is deemed okay, or do we help each individual maximize their safety, comfort and competence through means which are as ethical as possible? Those who argue for “getting more people on bikes” use cycling as a means to various ends: health, climate change, community livability, etc. Certainly those are all worthy goals, but it has led proponents to take some liberties with science, and misled many people about what factors are important both in increasing the number of cyclists and improving safety. They argue that increasing the numbers of cyclists will make cycling safer in spite of hazards created by some types of bicycle-specific infrastructure.

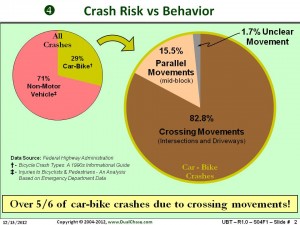

While it’s true that an increase in the numbers of bicyclists reduces the overall crash rate, the same is true of auto use and walking. Analysis of one study of a Danish bikeway found that the decrease in crash rate was less than would be predicted by Smeed’s Law. To put it in a more direct light: the number of crashes went up more than it would have if there had been no bikeway. Increasing numbers of bicyclists can improve safety, but only given the right circumstances. And even if safety in numbers through facilities does reduce the injury and fatality rates, if those same facilities actually cause some injuries and deaths, then we must question the ethics of such a strategy, especially if other strategies are available which would be less likely to cause harm.

What’s more, proponents assert that the right types of facilities significantly increase cycling. But the scientific support for this is also debatable. There are numerous factors that affect bicycle mode share, including climate, demographics, density, street network connectivity, terrain, the costs of owning and operating a motor vehicle, and most importantly, the presence of a college or university in a community. Do places with bicycle facilities get more cyclists, or do places with more cyclists get more bicycle facilities? It may be both. But if increases in cycling are due in large part to factors other than bikeways, then any reduction in the crash rate is indirectly due to those other factors, not to the bikeways, and if those bikeways cause or contribute to conflicts and crashes — which they do — then providing bikeways as means of increasing use and improving safety does not work and is in fact unethical.

Aside from the debate about whether or not bikeways improve safety, the need for cyclist training is essential. Florida emergency room data shows that two-thirds of adult bicyclist hospital admissions do not involve a collision with a motor vehicle. A significant portion of bicyclist/motorist crashes occur on local streets which will never see any sort of bicyclist-specific accommodation. Crashes involving turning and crossing conflicts occur whether one is cycling on a cycle track, a bike lane, a sidepath, a sidewalk, or on a road with no special accommodation at all. Training cyclists reduces their crash risk for all of these circumstances.

I — and other proponents of bicycle driving — am often assumed to be against all types of bicyclist-oriented infrastructure. That is not at all true. I support and very much enjoy shared use paths that run through independent rights-of-way. Short paths that connect local street networks. Bicycle boulevards. Bike routes and wayfinding that help people stay off of heavily traveled arterials. Shared lane markings on those arterials. Ensuring traffic signal systems detect bicyclists. Well-design traffic calming that keeps motorist speeds down or diverts motorist traffic. Even sidepaths can be a good solution in the right context. None of these treatments (if properly designed) encourages bicyclists to violate the rules for vehicular movement.

A Failure of Marketing, Not a Failure of Education

Another problem with the “it doesn’t work” claim is that it assumes cyclist education and training to be quite limited in definition. Adult cyclist education is presumed to be all the same. For many years, adult education was limited mostly to the League of American Bicyclists’ Traffic Skills 101 course and other descendants of John Forester’s Effective Cycling program. All other adult-oriented courses tend to be lumped together with them.

When detractors say, “We tried education; it doesn’t work (at getting enough people on bikes),” what they are likely seeing is not a failure of a particular curriculum, but a failure to effectively market a curriculum. Marketing is not merely advertising, it is determining what kind of product or service to provide in the first place and how to deliver it to the marketplace. And that, I believe, is where earlier bicyclist education programs have failed the most.

A number of years ago when Keri Caffrey and I were discussing what we’d like to see in adult cyclist education, we were frustrated with the materials we had to work with (the League curriculum) as well as with those who said education was of little value. We knew from direct experience teaching people that education had great potential, but also saw it fail for many individuals. To us that meant the problem was the teaching strategy, not education per se. Sitting in League education meetings and reading posts on the League Cycling Instructor email list, I saw how they were nibbling around the edges trying to incrementally improve a marginally effective curriculum, or arguing endlessly over minutiae such as whether or not to use a mirror. Hardly anyone was asking who their students were, what they want, how they learn best, how they want to manage their time, and how much they might value good training. The League’s curriculum seemed to be based more on what they wanted to teach than on what the customer wanted.

The League’s course is based on the original Effective Cycling curriculum developed by John Forester; many of the long-time League instructors have wanted to return to it. Effective Cycling was originally a 30-hour course, developed in the 1980s. It was intended to make someone into a highly competent sport rider, interested and capable of doing long-distance rides at higher speeds. The League whittled that down into two 10-hour courses, initially named Road I and Road II; later renamed Traffic Skills 101 and 201. While thousands have taken Road I and Traffic Skills 101, only a tiny number have followed up with the second course. TS 101 attempts to achieve the same goal in 10 hours — making an individual into a competent sport rider — as did the original 30-hour course. To do so, students are given a significant amount of information on bicycle components, bike fit, special clothing, minor repairs, hydration and nutrition, cadence and gearing. This leaves relatively little time for learning traffic skills.

For the average person who just wants to bike around his or her community at a comfortable speed, to run errands, visit friends, bike to work, or just have fun, most of those sport-cyclist-oriented topics are wasted time, and make cycling seem more complicated and elite than they want it to be.

CyclingSavvy was designed from the outset for the average adult who wishes to bike around his or her community at a comfortable and sociable speed; who prefers to avoid busy arterials but occasionally needs to use them for short distances to get to a destination or another quiet, low-volume street. Observers of our courses will see very few Lycra shorts or club jerseys, and quite a few bikes with raised handlebars rather than dropped ones.

Core Concepts

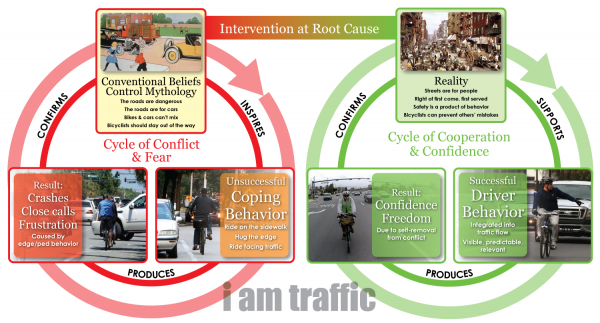

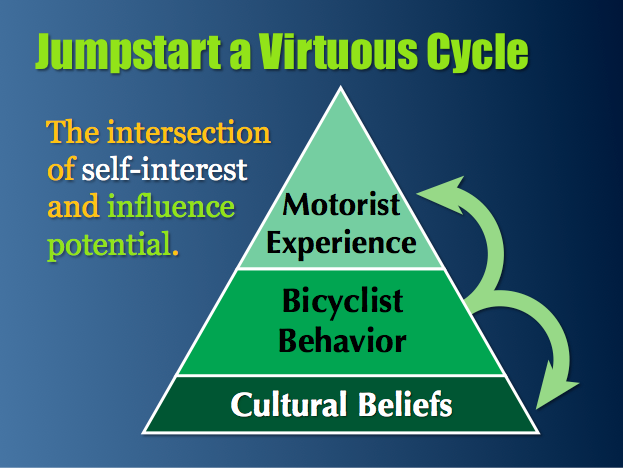

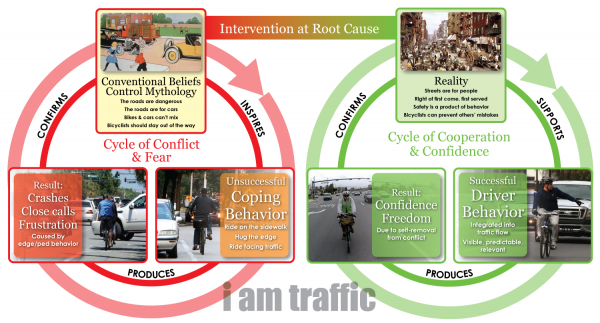

Fear was of course an essential issue we had to battle for those intimidated by the thought of cycling amid motor vehicle traffic. That fear is based on beliefs, not on an objective assessment of clearly organized data, so belief-change became a core goal of the curriculum.

As anyone who has waded into some of the hot-button issues of the day can tell you, beliefs don’t get overturned merely by presenting facts. How those facts are presented are at least as important as the facts themselves. So Keri and I did a lot of reading on how to influence people. The most important strategies are getting students to “own” key concepts by discovering the information themselves, and by having them publicly break the taboos of traffic cycling in a peer-supported setting. These strategies are unique to CyclingSavvy.

The other critical strategy was focusing on right-brained learning. Bicycling is a four-dimensional, kinesthetic and social experience, so learning must take place in all of those modes. Few people can fully translate a written or verbal description, or even a static illustration, into a coherent four-dimensional model in their heads. Animation and video get us much further with students. Story-telling in the classroom and the group road tour make it social, and of course on-bike training brings in the essential kinesthetic component.

How CyclingSavvy Differs From Effective Cycling

Since the rules for vehicular movement are nearly universal, especially in North America, the similarities between CyclingSavvy and Effective Cycling are far more prominent than their differences. But the differences do matter. They matter because most people want to minimize the amount of time they spend cycling on high-speed arterials. Depending on where one lives, much of one’s cycling can be accomplished on lower-speed, lower-volume streets. We like cycling on such streets as much for their ambiance as for safety (or the perception of safety). We can ride side-by-side and talk to one another. They tend to be more shaded (important here in the subtropics of Florida). There’s more to see and enjoy.

But sooner or later we need to cross or use a stretch of arterial to get to our destination or to the next network of quiet streets. CyclingSavvy’s strategies show cyclists how to use these arterials in the most stress-free ways possible. Examples include:

- Turning right on green even when a right on red is allowed. Doing so gives the cyclist the road to herself for blocks at a time. This can be enough time to get to the cyclist’s target intersection without having to negotiate lane changes with high-speed, high-volume traffic.

- Recognizing how traffic flows on the approaches to and exits from intersections. Early lane changes and strategic lane positioning can minimize the interaction and negotiation cyclists must do with motorists while changing lanes.

We also teach a strategy we call Control and Release which is only used for narrow, two-lane streets with significant traffic, or briefly near signals on multi-lane arterials. No-one likes to be the slow vehicle driver with the long line of faster drivers stewing and fuming behind them, but we also don’t like having cars and trucks squeeze past us at unsafe distances and speeds. So we control the lane so motorists don’t try to squeeze past in an unsafe manner, but then, if conditions allow, we move over and strategically allow motorists to pass at lower speed, or at locations where we get some extra width to work with. A similar strategy is also taught for multi-lane arterials when one gets stuck at the front at a red light, and a long queue of cars gets backed up behind us. We simply control the lane going through the intersection with the fresh green, but then pull over into the nearest driveway and let the big platoon of cars go by. After usually just 15 to 30 seconds the road clears out and we have it mostly to ourselves, and we can control a narrow lane without having traffic backed up behind us.

No Need for Speed

A criticism against “vehicular cycling” is that it requires cyclist “go fast” in order to integrate effectively with motorized traffic. While there are some proponents of integrated roadway cycling who hold that belief, Keri and I do not. The strategies we teach work just as well at 10 to 15 mph as they do at 20 to 25 mph. Indeed, a key point we make during the course is that slower speeds confer some key benefits to drivers of any type of vehicle: a more comprehensive view of the environment, better reaction time, and shorter braking distance.

Speed differential is a very over-rated factor. To a motorist driving 45 to 50 mph, it matters very little if a cyclist is going 10 mph or 20 mph. A 30 mph closing speed requires about 200 feet of perception, reaction and braking distance, while a 40 mph closing speed requires about 325 feet, but motorists can easily see cyclists from much farther than that. We’ve illustrated how unimportant this speed differential is with one of our students on a large, high-speed interchange between a high-speed arterial and a freeway. Lateral positioning in the lane is far more important than the relative speeds of the cyclist and motorist.

One need only read the student stories on the CyclingSavvy website to see that speed is of little consequence in getting the average non-sport cyclist to be confident in traffic..

Lane Width and Lane Position

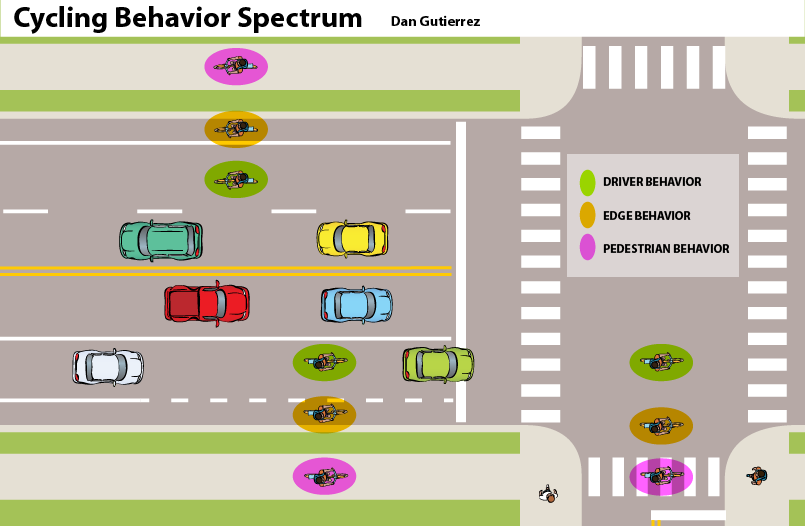

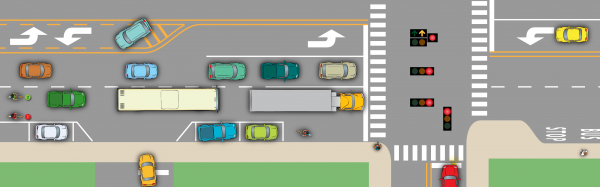

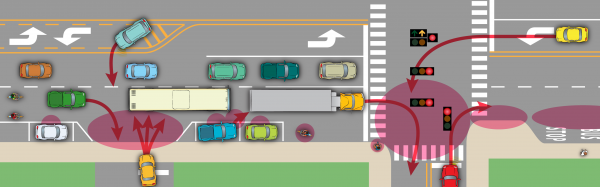

Forester in Effective Cycling and the League of American Bicyclists in their curricula tell cyclists to drive in the right wheel track when the lane is too narrow to share. What we have found, and what has been confirmed by research done by Dan Gutierrez and Brian DeSousa in southern California, is that the right tire track can sometimes be the worst position, particularly on higher-speed, multi-lane arterials. When motorists are driving at 45 mph and more, their decision zone — the range of distance behind the cyclist during which they are best able to decide whether to remain in the lane or change lanes — is quite a ways back due to the speed differential.

The problem is that from that distance, when a cyclist is driving in the right wheel track, it looks as though there is enough lane width for the motorists to pass within the lane. So some motorists will stay in the cyclist’s lane instead of changing lanes at the first opportunity. As they get closer to the cyclist they realize the width is not as great as they thought, but may have now lost the opportunity to change lanes. So they slow down a bit and pass within the lane. This results in a close pass at relatively high speed. Moving towards the center of the lane or left tire track makes it clear from a great distance that the motorist must change lanes to pass safely, so they do so at the earliest opportunity. By doing so they draw attention to the fact that there is something going on ahead, so the next motorist in the lane also sees the cyclist from a distance, and also changes lanes. This is best explained in this video.

Lane positioning is not a simple matter of either keeping right when the lane is wide enough to share or moving into the right wheel track when it is not. In a 9-foot lane the right wheel track is only about 6 feet from the left side of the lane, so the following motorist can see there’s not much width left in which to fit his vehicle. But in a 12-foot lane the right wheel track is about 8 feet from the left side, so many drivers will see that space as adequate. In CyclingSavvy we teach students to focus on how much space is available to his or her left, not to the right.

Changing Lanes

The lane changing instructions in Forester’s Effective Cycling strike us as overly complicated. They are also presented as though wide, sharable lanes are the norm. Lane changing is presented as first moving from the right side of the lane to the left side, then to the right side of the next lane, then to the left side of that new lane. That’s three movements with motorists passing on either side. How many would want to put themselves in such a situation?

What is far more common is for all the lanes to be too narrow to share. So the cyclist is already in the center of the right lane; scans, signals and then moves to the next lane, driving in the center of that one. One move, no lane sharing, very clear.

We also recognize that changing lanes when speeds and volumes are high is daunting and difficult for many people, so we provide a number of left turn strategies that eliminate the need to change lanes and negotiate with high-speed traffic: the “jughandle,” the “box turn,” and yes, even the pedestrian-style dismount-and-use-the-crosswalk (not recommended for Florida and other states where motorists treat pedestrians poorly).

Merges and Diverges

The League system waits until their second course (Traffic Skills 201) to teach strategies for merges and diverges. We include them in the core CyclingSavvy course because we think it is very unlikely that people will take a second course (a position clearly supported by the miniscule numbers of TS 201 courses taught). The fact that our students handle these features with ease during our road tours shows the wisdom of this approach. Interchanges and complex intersections can be enormous barriers to cyclists, so teaching them how to handle them is critical for attaining full mobility in their communities.

Our strategies for these features are very different from the League’s and Effective Cycling. We focus on helping the student read how traffic flows through such features, show them how to minimize converging paths with motorists and help motorists flow around them smoothly. Effective Cycling-based strategies have cyclists negotiate with motorists who are trying to change lanes or pass, often at relatively high speeds, all while sharing lanes. This strategy results in cyclists waiting too long to move into a defensible position and can in some circumstances create more traffic disruption and frustration among motorists. This is very stressful and intimidating for the cyclist.

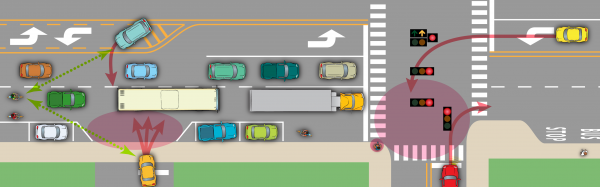

We show cyclists how to change lanes early so they have control of the lane they wish to be in well before the merging and diverging movements begin. This means motorists are more likely to flow around the cyclist on either side with ample clearance, rather than force negotiation with converging paths. As you can imagine, this is better explained through graphics and video than through text.

We show cyclists how to change lanes early so they have control of the lane they wish to be in well before the merging and diverging movements begin. This means motorists are more likely to flow around the cyclist on either side with ample clearance, rather than force negotiation with converging paths. As you can imagine, this is better explained through graphics and video than through text.

While on the road tour, we present students with numerous situations in which leaving the right edge, and even the right lane, is the best strategy. In effect we “wean” cyclists from the curb.

Bikeways

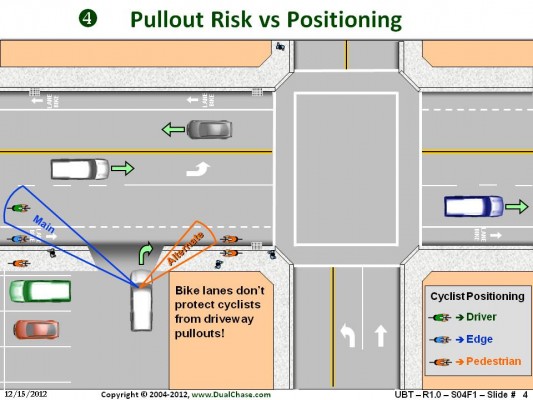

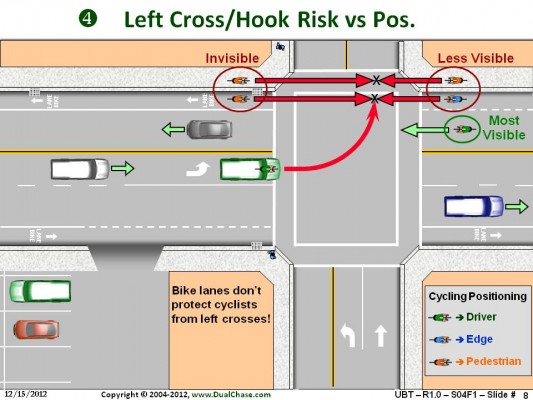

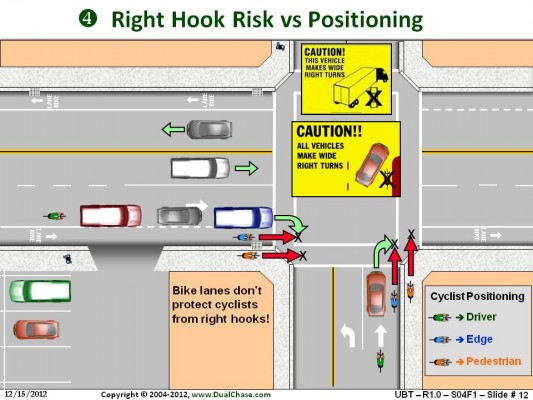

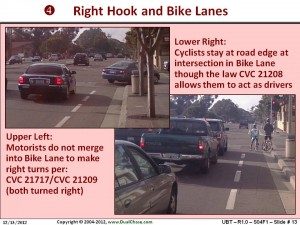

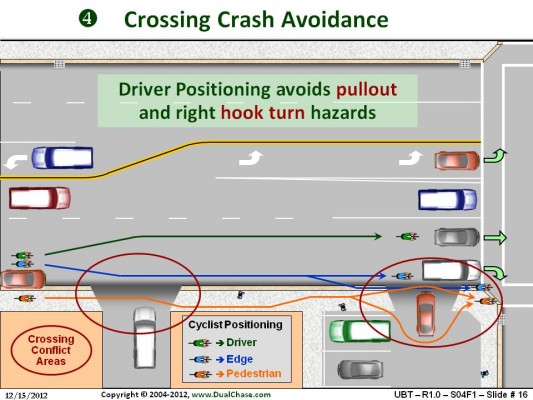

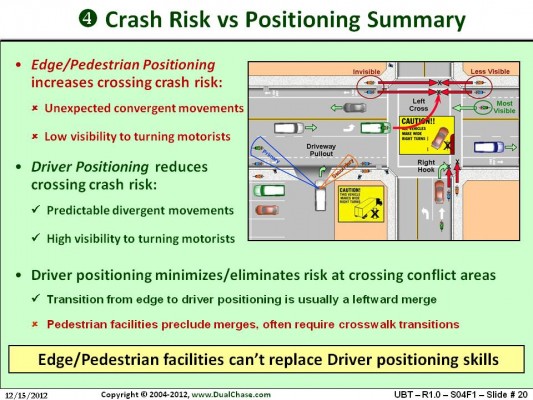

While we do spend a fair amount of time discussing problems that cyclists will encounter when using bike lanes (or cycle tracks or sidepaths), we do this in an objective manner devoid of politics and ideology. The conflicts are real and we simply provide practical solutions. Some of the students themselves, after learning of those conflicts, then question the wisdom of providing such facilities.

While we do spend a fair amount of time discussing problems that cyclists will encounter when using bike lanes (or cycle tracks or sidepaths), we do this in an objective manner devoid of politics and ideology. The conflicts are real and we simply provide practical solutions. Some of the students themselves, after learning of those conflicts, then question the wisdom of providing such facilities.

John Forester was openly hostile to bike lanes and sidepaths in his curriculum. The League has been fairly neutral in its curriculum, but very supportive of bike lanes in their advocacy. Some League Cycling Instructors have been frustrated with the contradictions between promoting integrated cycling on the one hand, while promoting bike lanes and other separate facilities on the other.

We must be clear though that we do not dismiss all bikeways. We enthusiastically support well-design paths in independent rights-of-way, short connector paths which help connect local street systems, bike boulevards, wayfinding systems, shared lane markings, and other on-road treatments that help cyclists while also supporting integrated roadway cycling. We’d even tolerate bike lanes on some arterials if they provided adequate width and a debris-free surface (but most don’t).

Communication

Rather than expecting motorists to be antagonistic towards cyclists, we strive to create an expectation of cooperation. What motorists want most from cyclists is clear communication on our intentions. We concentrate on communication strategies that assume the motorist is not clear on what we intend to do. (After all, if we watch most cyclists we can see rather quickly why motorists would be uncertain.)

Motorists appreciate clear communication, and going beyond the necessary signals and including ones of appreciation is one of the best forms of advocacy we can imagine.

Skill Building

While teaching Road I and Traffic Skills 101 courses we were frustrated by a number of things. We had only about an hour-and-a-half to teach a handful of skills, and the range of skills went from elementary to advanced. Experienced cyclists were bored until they got to the later skills, and the abrupt climb in difficulty intimidated many novices. Keri Caffrey and Lisa Walker had developed a series of skills for their women’s cycling club, the BOBbies (Babes On Bikes), which was more comprehensive and more progressive in pacing. These skills were incorporated and modified for CyclingSavvy, extending the bike-handling section to three hours. The sequencing of our skills provides interesting, fun skills for more experienced cyclists, while also building progressively enough such that novices are comfortable by the time they get to the more advanced skills.

As with the rest of our course, we strove to make this session fun, and most students report that it is.

Testing

We don’t. Most adults are not interested in meeting some score on a test. They just want to enjoy cycling and feel confident. Testing presents the opposite for many people; it creates an atmosphere of tension. Some people learn well but test poorly. Some test well, but don’t necessarily internalize the content completely.

We don’t. Most adults are not interested in meeting some score on a test. They just want to enjoy cycling and feel confident. Testing presents the opposite for many people; it creates an atmosphere of tension. Some people learn well but test poorly. Some test well, but don’t necessarily internalize the content completely.

Instead, we provide an experience out on the streets in real traffic. It is a group tour, but the cyclists drive through with a number of segments on their own. It is not merely a real traffic experience, but also a social experience. Students get to prove for themselves that the strategies we’ve shown them in the classroom actually work, and that experience is reinforced by the other students in the tour. Those who are concerned by an early, intimidating segment can always have an instructor accompany them, but they always volunteer to strike out on their own in later segments, and they all realize the kind of empowerment we’re striving to give them. Those who don’t test well are spared the tension of answering questions and meeting a minimum score, and those who might not have completely bought-in to the concepts have them reinforced by their peers.

Creating a Community

Rather than focusing on club rides which focus on speed and distance, we complement CyclingSavvy with social rides at low speeds around town: ice cream rides, cargo-bike rides to farmers’ markets, and simple social First Friday rides. They are open to cyclists of all skills and speeds. We give them structure and safety, so even those who haven’t taken a cycling  course such as ours can see and experience what is possible. They also learn some of the preferred back-street routes and “secret connectors.” Some of those social ride attendees come to CyclingSavvy classes. We are happy to use our area’s trails and connector paths, but prefer to avoid streets with bike lanes as they don’t allow us to ride side-by-side. Bike lanes also present more conflicts for groups than they do for solo cyclists.

course such as ours can see and experience what is possible. They also learn some of the preferred back-street routes and “secret connectors.” Some of those social ride attendees come to CyclingSavvy classes. We are happy to use our area’s trails and connector paths, but prefer to avoid streets with bike lanes as they don’t allow us to ride side-by-side. Bike lanes also present more conflicts for groups than they do for solo cyclists.

Perhaps this strategy — of leading people towards confidence and competence rather than providing facilities which make people feel safer without actually addressing the real conflicts — won’t get as many people on bicycles, or do so as quickly, but we can feel sure that we are supporting our principles rather than subverting them.

Education Is a Gift

“You have such gifts that are important. Just like every species has an important gift to give to an ecosystem, and the extinction of any species hurts everyone. The same is true of each person; that you have a necessary and important gift to give.” — Charles Eisenstein

The nature of a gift is “more for you means more for me.” But look at how bike lanes and cycle tracks affect people. Some non-cyclists see them as taking away from “their” roads. Or they see them as something they were forced to buy (by the government) and give to someone else. Then they encounter them, and the cyclists who use them, and find them confusing and frustrating, especially at intersections. So bike lanes and cycle tracks take the “more for me means less for you” approach. It becomes a turf war. And of course they can only “work” where they are installed, so we “need” to keep taking more and more space from others to get more people on bikes. I spent 15 years trying to prove that bike lanes could increase cycling while improving cyclist safety. In the process I learn they do not. (And other types of bikeways running alongside roadways are even more problematic.)

You cannot convince me something works when every day I see it not working. I see wrong-way cyclists in bike lanes; I get right-hooked by motorists when biking in them myself; I see other cyclists setting themselves up for conflicts. I see the crash reports. While some of these problems are in spite of the bike lanes; many are, to varying degrees, generated by them. And they don’t eliminate many of the real problems cyclists experience. That is not a gift. To anyone.

CyclingSavvy encourages cooperation between road users. Once taught, a cyclist can figure out for herself how to manage any road or intersection. Yes, some motorists get upset seeing cyclists take such an assertive approach, but they eventually realize such cyclists are predictable and cooperative, and that they only need to adhere to the same rules they’ve been following when interacting with other motorists. We’ve also heard from many motorists who find our strategies predictable and cooperative from the outset. So CyclingSavvy is not only a gift to cyclists, but to motorists as well. Those who think cyclists should naturally be antagonistic towards “cagers” might do well to realize that virtually all the new bicyclists we might invite will be coming from the motoring population. How do we convince motorists to become cyclists when they perceive cyclists as adversaries or incompetent?

Those of us who teach CyclingSavvy believe we have a gift we can share. Those we’ve shared it with have thanked us in many ways. That gift is the knowledge that they can hop on a bicycle at any time and go wherever they wish with confidence. By getting on the bike they meet new friends, learn of wonderful new places they didn’t know existed, improve their health, spend quality time with their families, reduce their carbon footprints, and save money. Rather than waiting for the government to provide facilities which don’t work as advertised, they gain all of those benefits as soon as they want them.

You cannot convince me something does not work when every day I see it working. I see people who used to be afraid biking wherever and whenever they wish. I hear their stories of enjoying life by bike. I hear them exclaim how much easier and stress-free it is now to bike. Real, sincere and practical gifts always beat white elephants.

The reward for the bicyclist is tremendous: empowerment for unlimited travel. But the reward for those of us wanting to encourage bicycling is also significant. This bicyclist tells stories, too. She tells stories about all the places she goes on her bike, how much better she feels when she arrives at a destination, how easy and rewarding it is to use a bike for transportation and how courteous her fellow road users are. She’s positively connected to her community. Her enthusiasm is infectious. It inspires her friends to dust off their bikes and try a trip to the park or the store, too. If they implement her style of riding, they, too, will be empowered by success. New positive stories will begin to edge out the old negative ones.

The reward for the bicyclist is tremendous: empowerment for unlimited travel. But the reward for those of us wanting to encourage bicycling is also significant. This bicyclist tells stories, too. She tells stories about all the places she goes on her bike, how much better she feels when she arrives at a destination, how easy and rewarding it is to use a bike for transportation and how courteous her fellow road users are. She’s positively connected to her community. Her enthusiasm is infectious. It inspires her friends to dust off their bikes and try a trip to the park or the store, too. If they implement her style of riding, they, too, will be empowered by success. New positive stories will begin to edge out the old negative ones.