Co-author: Steven Goodridge.

What would you do?

You are driving your car along a narrow two-lane road when a cyclist comes into view up ahead. Of course, you are a lawful, responsible, and respectful driver. You recognize that the lane is not wide enough to safely pass within it, so you slow down. If your sight lines are limited, you follow behind the cyclist until sight lines open up. If you are approaching an intersection where you might have to stop, then you follow behind the cyclist until you are past that point as well. If there is oncoming traffic, you wait for it to clear. Then, you move into the oncoming lane, accelerate, and pass the cyclist, leaving them plenty of room for safety and comfort. When you are safely past the cyclist and their forward right-of-way, you move back into the proper lane and continue on your way. No problem, right? Just another everyday driving maneuver.

But what if a traffic engineer decided to have a solid double yellow line applied down the middle of that road? Wouldn’t your passing maneuver be a violation of traffic law? So what do you do? Do you call the police to complain about the cyclist? Do honk or yell at the cyclist to move over? Do you try to squeeze past the cyclist without moving into the oncoming lane? Of course not. You’re a lawful, responsible, respectful driver. Do you follow behind the cyclist until your route diverges from theirs or you reach a point where the design of the road changes? That’s certainly a safe and legal option, but it is inconvenient and it seems unnecessary, since you can see an opportunity to pass safely. Or do you just take the first opportunity to pass safely, legal or not?

If you are like most motorists, you take the first opportunity to pass the cyclist safely, regardless of the stripe. After all, the purpose of the solid yellow line is to indicate where it is unsafe to pass, and the purpose of prohibiting drivers from crossing a solid yellow line to pass another driver is to prevent unsafe passing. So if it is safe to pass, then why is the solid yellow line there in the first place?

How did we get here?

Our surface streets have carried a wide variety of low-speed vehicles – horse drawn carriages, bicycles, tractors – since long before the popularity of motoring. Our traffic laws protect the right to drive these slower vehicles while also defining the limited privileges of overtaking for drivers who want to travel faster. For instance, overtaking drivers are prohibited from moving into the path of oncoming traffic or moving left of center where short sight distances would make this unsafe. The traffic laws clearly state that a driver wishing to pass another driver must wait behind until conditions are safe for passing without interfering with other travelers.

As motoring became increasingly popular over the last century, motor-vehicle crashes took a tremendous toll in human life. One of the most devastating crash types involves a high-speed motorist swerving or drifting left of center on a two-way roadway and colliding head-on with oncoming traffic. Highway engineers discovered that marking a stripe down the center of such roadways reduced such collisions by helping drivers keep track of their position relative to the center of the roadway. Marking of stripes in the center of roads that carry traffic at high speeds or high volumes eventually became standard practice. These markings are an early example of “traffic controls” that traffic engineers install with the intent to encourage safe operation in compliance with the traffic laws. Over the decades, traffic engineers have added more and more traffic controls to roadways, sometimes with good results and sometimes with unintended consequences. Because the traffic engineering profession is half hard science and half social experiment, the full effects of traffic controls sometimes take time to reveal themselves.

In response to motorist errors, traffic engineers began marking no-passing zones in areas where the sight distance was inadequate to safely pass a vehicle traveling just below the maximum posted speed limit.

Some collisions that occur on two-lane roads are caused by motorists attempting to pass other drivers in when oncoming traffic is too close, but might be beyond the passing motorist’s sight distance when the maneuver begins. Although the passing law requires drivers to heed the sight distance required to pass safely, some drivers underestimate the sight distance needed, particularly when passing traffic moving at high speeds. (Other drivers choose to risk passing regardless of clearly inadequate sight distance.) In response to this, traffic engineers began marking no-passing zones in areas where the sight distance was too short for passing a vehicle traveling just below the maximum posted speed limit 1. A solid stripe became the standard marking for no-passing zones, with dashed markings used elsewhere. Some states, such as Vermont and Missouri, adopted traffic laws that treated the solid centerline as a warning rather than a statutory prohibition against passing, but most states adopted laws that prohibited passing on a two-lane road wherever a solid centerline was present.

Over time, solid centerlines proliferated over a larger percentage of roadway miles. On many two-lane roads, solid centerlines continue for miles at a time, with no dashed sections at all.

Over time, solid centerlines proliferated over a larger percentage of roadway miles. Engineers marked them extending out several hundred feet from intersections, in areas with driveways, and anywhere else that the engineers considered unsafe for passing, particularly at high speed. The formulas and tables used to determine where to place solid centerlines assumed that the vehicle being passed was traveling near the maximum posted speed limit1, so that dashed centerlines, indicating permission to pass, became quite rare. On many two-lane roads, solid centerlines continue for miles at a time, with no dashed sections at all. Passing of same-direction motorists on two-lane roads declined over time, partly because of the scarcity of legal passing zones, but also due to greater availability of multi-lane roads for longer route segments. Toward the end of the 20th century, traffic engineers saw passing zones to be less important as the amount of low-speed traffic declined (toward extinction, some may have presumed) and many of the motorists who did pass on two-lane roads were exceeding the speed limit.

The markings that traffic engineers placed on most miles of two-lane roads did not communicate a reasonably convenient process for passing low-speed vehicles.

Yet low-speed vehicles did not disappear from the roadways. Bicycles, thought by many in the mid-20th century to be obsolete, suitable only as children’s toys, later resurged as an economical, healthy, energy-efficient travel mode. Mopeds and scooters continued to be used as an affordable alternative to motorcycles. Horse-drawn carriages remained in use by traditionalist groups and equestrian tour operators. Farm tractors and construction vehicles were joined by new types of short-range electric utility vehicles. Laws throughout the country recognize a general right to travel on public roadways. At I Am Traffic, we are aware of some troubling infringements on this right, but the law does generally recognize that the public’s right to the road is not dependent on speed capability. But the markings that traffic engineers placed on most miles of two-lane roads did not communicate a reasonably convenient process for passing low-speed vehicles. The system is broken.

In some places, highway engineers have attempted to make two-lane roads wider to accommodate passing of some types of slower vehicles, but most roads cannot be widened due to economics. Instead, drivers of low-speed vehicles often become scapegoats for the dysfunctional nature of the road design and lane markings. Because traffic engineers have not considered the requirement to pass low-speed vehicles when designing the roads, many in government treat drivers of such vehicles as “unintended users” and marginalize their use of typically marked roadways.

What’s the problem?

In most of the United States, a motorist is not clearly permitted to cross a solid centerline to pass a cyclist when safe. Yet practically all drivers do, rather than continue to follow the cyclist at reduced speed. Drivers recognize that current striping policies for no-passing zones are overly restrictive in the context of low-speed vehicles. Mathematical analysis bears this out. For instance, safely passing a motorist traveling at 35 mph on a 45 mph road requires a sight distance 600 feet longer than passing a 15 mph bicyclist on the same road 2.

There is a common provision permitting a driver to cross a solid centerline to pass an “obstruction”. Does a cyclist qualify as an obstruction? Some police departments take this interpretation while others do not. But police department policy is not law and for many reasons cannot take the place of law.

Some departments will apply a common exception for passing an “obstruction” to slow moving vehicles.

Considering cyclists to be obstructions is not necessarily good for cyclists, even if it seems to work in particular cases.

Moreover, considering cyclists to be obstructions is not necessarily good for cyclists, even if it seems to work in particular cases. Other drivers engaged in normal driving behavior are not referred to as obstructions, and referring to cyclists this way is degrading and can lead to further ill treatment in the future. It can even lead to bad outcomes in court proceedings, where the characterization of cyclists as obstructions might be carried into a different context.

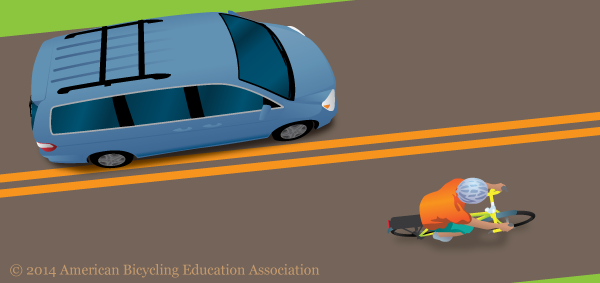

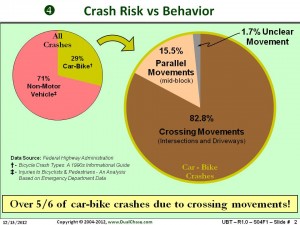

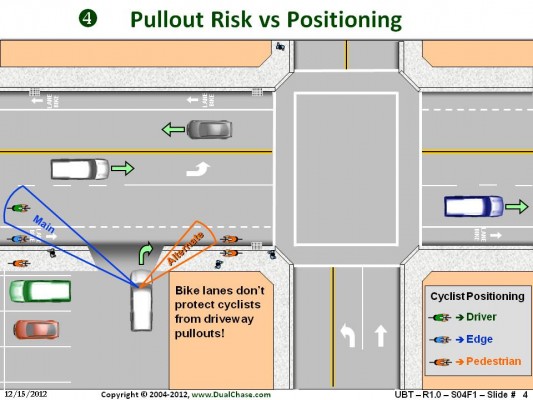

The legal ambiguity around crossing a solid centerline is a source of conflict for cyclists, motorists, police officers, and driving instructors. Motorists can be unnecessarily inconvenienced because they believe that they are not allowed to pass a cyclist. Their frustration can lead to resentment and hostility toward cyclists. It can even lead to riskier behavior and crashes. A motorist might honk or yell at cyclists or might buzz them to avoid crossing a solid centerline. In the worst cases, motorists have attempted to squeeze past cyclists within the same lane and fatally struck the cyclists.

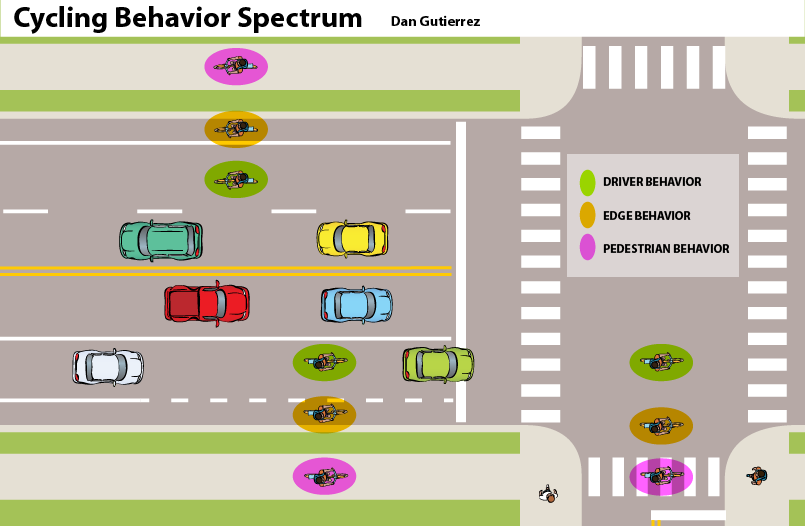

A cyclist can feel anxious about motorists following behind for too long, as can happen if a motorist believes that passing is prohibited. The cyclist can feel obligated to move to the edge and encourage motorists to squeeze past at an unsafe distance. There is a common belief that cyclists are legally obligated to enable passing regardless of the inconvenience or danger to themselves. This belief is completely false – cyclists’ obligation to facilitate passing is no greater than for other drivers – but the legal ambiguity about crossing a solid centerline exacerbates this belief. People are entitled to assume that the law and the design of roads make sense and will not lead to absurd situations. A motorist who is doing everything right, but can’t get around a cyclist, even if traffic is light, might understandably assume that the cyclist is doing something wrong. Police officers are vulnerable to the same confusion, and may stop or ticket cyclists for bogus infractions such as “impeding traffic” (which by law only applies to drivers traveling more slowly than they reasonably can).

The ambiguity about crossing a solid centerline frustrates driving instructors who teach cyclists or motorists about safely interacting with the other. In a typical encounter between a cyclist and a motorist on a narrow two-lane road, the safe and effective technique for the motorist is to wait behind the bicyclist until it is safe to move into the oncoming lane to pass. The safe and effective behavior for the cyclist consists of controlling the lane (taking a position in the lane far enough leftward to discourage motorists from attempting to pass) while there is oncoming traffic or any other condition that would make passing unsafe, and at other times encouraging the motorist, through a more rightward position and/or gestures, to move into the oncoming lane to pass. This technique is known as Control and Release. However, discussion of these techniques is frequently derailed by arguments over whether it is legal for the motorist to cross a solid centerline to pass a cyclist and when it is legal for a cyclist travel on a road under any conditions in which motorists cannot legally pass.

Can we fix this thing?

The long-term solution is for traffic engineers to include low-speed vehicles as design vehicles on all ordinary surface roads and to provide appropriate passing facilities depending on context. For instance, important through roads intended to support high speed traffic might warrant more convenient passing facilities than low-speed, low-volume, local streets. Such widespread engineering changes will not be achieved any time soon. In the meantime, an easier fix is needed. A prime candidate for such a fix is a provision in traffic codes that explicitly permits a driver to cross a solid centerline to pass under appropriate conditions. Some states have already implemented this fix. Colorado3, Maine4, Mississippi5, Ohio6, Pennsylvania7, Utah8 and Wisconsin9, for example, have added provisions to their respective traffic codes explicitly allowing drivers to cross a solid centerline to pass a slow-moving vehicle, or a bicyclist specifically, under safe conditions.

The vast majority of motorists are already crossing solid centerlines to pass cyclists today. What isn’t happening is a substantive public discussion about how to do it safely.

We propose that prohibitions on crossing solid centerlines be relaxed by adding an exception for passing vehicles traveling at a sufficiently low speed. In Ohio, for example, this speed threshold is half the maximum posted speed limit. Such an exception would be applicable to passing tractors, construction vehicles and horse-drawn carriages, in addition to bicycles. Most motorists already cross solid centerlines to pass all of these vehicles when safe. However, Ohio’s exception is not entirely satisfactory. It is not uncommon for a cyclist’s speed to be greater than half the maximum posted speed limit, while still being unnecessarily slow for a following motorist. For example, it is well within the range of normal conditions for cyclist to be traveling at 20mph in 30mph zone or even 30mph in a 50mph zone (going down a hill, for example). If the road is straight, then sight distance would likely be adequate for a motorist to pass this cyclist safely and without exceeding the maximum posted speed limit.

Model No-Passing-Zone Exception

When passing a pedestrian, bicycle, tractor, or other slow moving vehicle, the operator of a vehicle may drive on the left side of the center of a roadway in a no-passing zone when such movement can be made in safety and without interfering with or endangering other traffic on the highway.

Alternatively, states could redefine the meaning of the solid centerline from a statutory prohibition on passing to a warning that passing may be unsafe. This is already the case in some states, such as Vermont (the Vermont statute requires signs, not solid striping alone, to define a no-passing zone). All of the other laws restricting passing due to oncoming traffic and limited sight distance would still apply.

We ask that legislators modernize their passing laws to reflect safe and practical passing practices, and that cycling advocates make a priority of lobbying them to do so.

The vast majority of motorists are already crossing solid centerlines to pass cyclists today. What isn’t happening is a substantive public discussion about how to do it safely. Changing the law to reflect prudent behavior will facilitate this discussion as well as better public education and more effective law enforcement. We at I Am Traffic believe that relaxing the solid centerline no-passing rule is essential to reducing sideswipes, unsafe close passing, and harassment of bicyclists on two-lane roads. We ask that legislators modernize their passing laws to reflect safe and practical passing practices, and that cycling advocates make a priority of lobbying them to do so.

Footnotes

1. NCHRP Report 605, Passing Sight Distance Criteria, Transportation Research Board, 2008. http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_605.pdf↩

2. Consider a driver planning a pass on a 45 mph road. Observation of real-world behavior shows that drivers take an average of seven-seconds to pass a 15 mph bicyclist (with a speed differential of 10 mph), but an average of ten seconds to pass a 35 mph car. A seven second pass at 25 mph covers about 256 feet worst case (ignoring acceleration). By comparison, a ten second pass at 45 mph covers about 660 feet. An oncoming 45 mph driver travels 462 feet in seven seconds and 660 feet in 10 seconds. The required safe passing sight distance in the average bicyclist case is therefore about 600 feet shorter than in the average motorist case. Also, the slower passing speed is safer, should the passing driver misjudge; the oncoming driver will have more time and distance to reduce speed and “cooperate” with the pass as is often the case whrn passing a stationary obstruction. While the law prohibits a passing driver from interfering with an oncoming driver and requiring that driver to slow, this interference is much less dangerous when passing a slow bicyclist than when passing a fast motorist. This is why there are so few crashes involving oncoming vehicles when drivers are passing cyclists on two-lane roads.↩

3. Colorado No-Passing-Zone Exception

42-4-1005. Limitations on overtaking on the left

(1) No vehicle shall be driven to the left side of the center of the roadway in overtaking and passing another vehicle proceeding in the same direction unless authorized by the provisions of this article and unless such left side is clearly visible and is free of oncoming traffic for a sufficient distance ahead to permit such overtaking and passing to be completed without interfering with the operation of any vehicle approaching from the opposite direction or any vehicle overtaken. In every event the overtaking vehicle must return to an authorized lane of travel as soon as practicable and, in the event the passing movement involves the use of a lane authorized for vehicles approaching from the opposite direction, before coming within two hundred feet of any approaching vehicle.

(2) No vehicle shall be driven on the left side of the roadway under the following conditions:

(a) When approaching or upon the crest of a grade or a curve in the highway where the driver’s view is obstructed within such distance as to create a hazard in the event another vehicle might approach from the opposite direction;

(b) When approaching within one hundred feet of or traversing any intersection or railroad grade crossing; or

(c) When the view is obstructed upon approaching within one hundred feet of any bridge, viaduct, or tunnel.

(3) The department of transportation and local authorities are authorized to determine those portions of any highway under their respective jurisdictions where overtaking and passing or driving on the left side of the roadway would be especially hazardous and may by appropriate signs or markings on the roadway indicate the beginning and end of such zones. Where such signs or markings are in place to define a no-passing zone and such signs or markings are clearly visible to an ordinarily observant person, no driver shall drive on the left side of the roadway within such no-passing zone or on the left side of any pavement striping designed to mark such no-passing zone throughout its length.

(4) The provisions of this section shall not apply:

(a) Upon a one-way roadway;

(b) Under the conditions described in section 42-4-1001 (1) (b);

(c) To the driver of a vehicle turning left into or from an alley, private road, or driveway when such movement can be made in safety and without interfering with, impeding, or endangering other traffic lawfully using the highway; or

(d) To the driver of a vehicle passing a bicyclist moving the same direction and in the same lane when such movement can be made in safety and without interfering with, impeding, or endangering other traffic lawfully using the highway.↩

4. Maine No-Passing-Zone Exception

Title 29-A: MOTOR VEHICLES HEADING: PL 1993, C. 683, PT. A, §2 (NEW); PT. B, §5 (AFF)

Chapter 19: OPERATION HEADING: PL 1993, C. 683, PT. A, §2 (NEW); PT. B, §5 (AFF)

Subchapter 1: RULES OF THE ROAD HEADING: PL 1993, C. 683, PT. A, §2 (NEW); PT. B, §5 (AFF)

§2070. Passing another vehicle

1. Passing on left. An operator of a vehicle passing another vehicle proceeding in the same direction must pass to the left at a safe distance and may not return to the right until safely clear of the passed vehicle. An operator may not overtake another vehicle by driving off the pavement or main traveled portion of the way.

[ 1997, c. 653, §11 (AMD) .]

1-A. Passing bicycle or roller skier. An operator of a motor vehicle that is passing a bicycle or roller skier proceeding in the same direction shall exercise due care by leaving a distance between the motor vehicle and the bicycle or roller skier of not less than 3 feet while the motor vehicle is passing the bicycle or roller skier. A motor vehicle operator may pass a bicycle or roller skier traveling in the same direction in a no-passing zone only when it is safe to do so.↩

5. Mississippi No-Passing-Zone Exception

MS Code § 63-3-1309 (2013)

(1) While passing a bicyclist on a roadway, a motorist shall leave a safe distance of not less than three (3) feet between his vehicle and the bicyclist and shall maintain such clearance until safely past the bicycle.

(2) A motor vehicle operator may pass a bicycle traveling in the same direction in a nonpassing zone with the duty to execute the pass only when it is safe to do so.

(3) The operator of a vehicle that passes a bicyclist proceeding in the same direction may not make a right turn at any intersection or into any highway or driveway unless the turn can be made with reasonable safety.↩

6. Ohio No-Passing-Zone Exception

4511.31. Hazardous zones

(A) The department of transportation may determine those portions of any state highway where overtaking and passing other traffic or driving to the left of the center or center line of the roadway would be especially hazardous and may, by appropriate signs or markings on the highway, indicate the beginning and end of such zones. When such signs or markings are in place and clearly visible, every operator of a vehicle or trackless trolley shall obey the directions of the signs or markings, notwithstanding the distances set out in section 4511.30 of the Revised Code.

(B) Division (A) of this section does not apply when all of the following apply:

(1) The slower vehicle is proceeding at less than half the speed of the speed limit applicable to that location.

(2) The faster vehicle is capable of overtaking and passing the slower vehicle without exceeding the speed limit.

(3) There is sufficient clear sight distance to the left of the center or center line of the roadway to meet the overtaking and passing provisions of section 4511.29 of the Revised Code, considering the speed of the slower vehicle.↩

7. Pennsylvania No-Passing-Zone Exception

§ 3307. No-passing zones.

(a) Establishment and marking.–The department and local authorities may determine those portions of any highway under their respective jurisdictions where overtaking and passing or driving on the left side of the roadway would be especially hazardous and shall by appropriate signs or markings on the roadway indicate the beginning and end of such zones and when the signs or markings are in place and clearly visible to an ordinarily observant person every driver of a vehicle shall obey the directions of the signs or markings. Signs shall be placed to indicate the beginning and end of each no-passing zone.

(b) Compliance by drivers.–Where signs and markings are in place to define a no-passing zone as set forth in subsection (a), no driver shall at any time drive on the left side of the roadway within the no-passing zone or on the left side of any pavement striping designed to mark a no-passing zone throughout its length.

(b.1) Overtaking pedalcycles.–It is permissible to pass a pedalcycle, if done in accordance with sections 3303(a)(3) (relating to overtaking vehicle on the left) and 3305 (relating to limitations on overtaking on the left).

(c) Application of section.–This section does not apply under the conditions described in section 3301(a)(2) and (5) (relating to driving on right side of roadway).↩

8. Utah No-Passing-Zone Exception

41-6a-708. Signs and markings on roadway — No-passing zones — Exceptions.

(1) (a) A highway authority may designate no-passing zones on any portion of a highway under its jurisdiction if the highway authority determines passing is especially hazardous.

(b) A highway authority shall designate a no-passing zone under Subsection (1)(a) by placing appropriate traffic-control devices on the highway.

(2) A person operating a vehicle may not drive on the left side of:

(a) the roadway within the no-passing zone; or

(b) any pavement striping designed to mark the no-passing zone.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply:

(a) under the conditions described under Subsections 41-6a-701(1)(b) and (c); or

(b) to a person operating a vehicle turning left onto or from an alley, private road, or driveway.

41-6a-701. Duty to operate vehicle on right side of roadway — Exceptions.

(1) On all roadways of sufficient width, a person operating a vehicle shall operate the vehicle on the right half of the roadway, except:

…

(c) when overtaking and passing a bicycle or moped proceeding in the same direction at a speed less than the reasonable speed of traffic that is present requires operating the vehicle to the left of the center of the roadway subject to the provisions of Subsection (2)

↩

9. Wisconsin No-Passing-Zone Exception

346.09 Limitations on overtaking on left or driving on left side of roadway.

(3)

(a) Except as provided in par. (b), the operator of a vehicle shall not drive on the left side of the center of a roadway on any portion thereof which has been designated a no-passing zone, either by signs or by a yellow unbroken line on the pavement on the right-hand side of and adjacent to the center line of the roadway, provided such signs or lines would be clearly visible to an ordinarily observant person.

(b) The operator of a vehicle may drive on the left side of the center of a roadway on any portion thereof which has been designated a no-passing zone, as described in par. (a), to overtake and pass, with care, any vehicle, except an implement of husbandry or agricultural commercial motor vehicle, traveling at a speed less than half of the applicable speed limit at the place of passing.↩