“She is the bellwether for: ‘Do we have the right to use the road[way] or not?’ Not when it’s fashionable, not when it’s yuppies in Portland, but when it is a single mom who needs to get to her job.” — John Schubert

In May, we shared the case of Cherokee Schill, a single mom in Kentucky whose only means of transportation is a bicycle, and whose only viable route to work was a nasty U.S. Highway. Cherokee has been systematically targeted by Jessamine County law enforcement. She was charged with careless driving for operating her bicycle in the right-hand travel lane. Her case went to trial in September. Despite the fact that all four expert witnesses (two for the prosecution and two for the defense) testified that the shoulder was unsafe and that the way Cherokee was riding on that road was the safest way to ride, the judge sided with the prosecutor and upheld the citations for careless driving.

There are important issues in this case that are not well understood, and that have been further obscured by a vocal faction of detractors. This post will discuss those issues.

First, for some background, listen to the Outspoken Cyclist radio interview with expert witness John Schubert. John recaps the trial beginning at 10:20 in the podcast.

FACTS & ISSUES

1) Statutory definitions are important.

Kentucky definitions for the key terms used this case are consistent with other U.S. states.

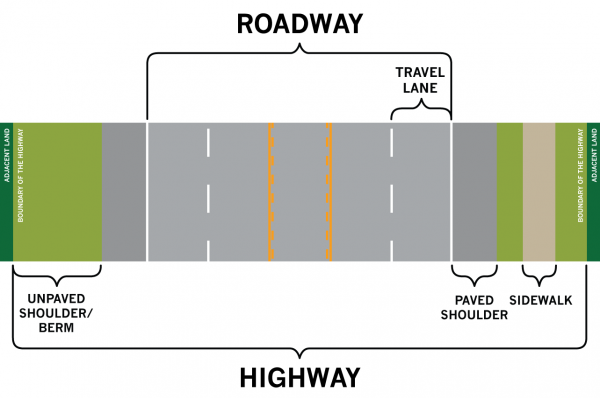

“Highway”]KRS 189.010 (3) Highway means any public road, street, avenue, alley or boulevard, bridge, viaduct, or trestle and the approaches to them.

“Roadway”]KRS 189.010 (10) Roadway means that portion of a highway improved, designed, or ordinarily used for vehicular travel, exclusive of the berm or shoulder.

KRS 189.010 (19) (a) Vehicle includes:

- All agencies for the transportation of persons or property over or upon the public highways of the Commonwealth; and

- All vehicles passing over or upon the highways.

(b) Motor vehicle includes all vehicles, as defined in paragraph (a) of this subsection except:

- Road rollers;

- Road graders;

- Farm tractors;

- Vehicles on which power shovels are mounted;

- Construction equipment customarily used only on the site of construction and which is not practical for the transportation of persons or property upon the highways;

- Vehicles that travel exclusively upon rails;

- Vehicles propelled by electric power obtained from overhead wires while being operated within any municipality or where the vehicles do not travel more than five (5) miles beyond the city limits of any municipality; and

- Vehicles propelled by muscular power.

In summary: A bicycle is a vehicle. A bicycle is not a motor vehicle. The roadway (which, in the case of U.S. 27, consists of travel lanes and turn lanes) is the part of the highway intended for vehicles to use. All vehicles, not just motor vehicles.

2) Sloppily written statutes can be exploited to abuse citizens.

The following three statutes were used by the prosecutor to make his case.

Slow vehicle statute language is inconsistent with definitions”

KY 189.300

(2) The operator of any vehicle moving slowly upon a highway shall keep his vehicle as closely as practicable to the right-hand boundary of the highway, allowing more swiftly moving vehicles reasonably free passage to the left.

See the diagram and definition above. The right-hand boundary of the highway is the edge of the public right-of-way. It seems unlikely the KY legislature expected slow vehicles (including motor vehicles) to be operated in the grass berm, or on a sidewalk. The more common language for a slow vehicle law is found in the Uniform Vehicle Code:

UVC 11-301 (b) Upon all roadways any vehicle proceeding at less than the normal speed of traffic at the time and place and under the conditions then existing shall be driven in the right-hand lane then available for traffic, or as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway, except when overtaking and passing another vehicle proceeding in the same direction or when preparing for a left turn at an intersection or into a private road, alley, or driveway. The intent of this subsection is to facilitate the overtaking of slowly moving vehicles by faster moving vehicles.

Slow vehicles are to use the right lane or drive as close as practicable to the right edge of the roadway. The latter applying only to roads without lanes. Unfortunately, KY has not adopted the UVC, or at least not a recent version of it, and remains among a handful of states that use language that is inconsistent with statutory definitions of highway and roadway. We know of no other cases where such language was used to selectively discriminate against a bicyclist or driver of any other slow vehicle using the roadway.

Bicyclists MAY use the shoulder

Kentucky Administrative Regulation (KAR) permits, but does not require, bicyclists to use the shoulder.

Section 9. Operation of Bicycles. A bicycle shall be operated in the same manner as a motor vehicle except the following traffic conditions shall apply:

(1) A bicycle may be operated on the shoulder of a highway;

(2) If a highway lane is marked for the exclusive use of bicycles, the operator of a bicycle shall use the lane whenever feasible;

(3) Not more than two (2) bicycles shall be operated abreast in a single highway lane.

The use of “may” in statute is permissive, not mandatory. A requirement to use the shoulder would be worded as “shall.” Nonetheless, this permission was used against Cherokee. The prosecutor argued that because 189.300 (2) required slow vehicles to be kept as close as practicable to the right hand boundary of the highway AND bicyclists are allowed to use the shoulder, the bicyclist is then required to drive on the shoulder.

Requirement to drive carefully

KY 189.290 Operator of vehicle to drive carefully.

(1) The operator of any vehicle upon a highway shall operate the vehicle in a careful manner, with regard for the safety and convenience of pedestrians and other vehicles upon the highway.

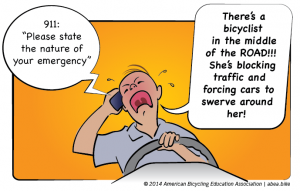

Cherokee wasn’t charged with a simple traffic ticket, she was charged with careless driving. The case was built upon the purported careless behavior of other drivers reacting poorly to her presence on the road. Yes, this woman on a bicycle was failing to operate with regard for the safety and convenience of people enclosed in multi-ton vehicles because motorists’ careless behavior, driven by incompetence or aggression, might endanger other motorists. I have no idea how anyone could argue that with a straight face, but there you go.

In summary, Cherokee was found guilty of careless driving because the law allows her to use the shoulder. In choosing not to use the shoulder, she disregarded the “safety and convenience” of people who are incapable of simply changing lanes to pass a slower vehicle without having a temper tantrum.

3) A bicyclist’s decisions about her own safety are subject to being overruled by people who know nothing about bicycling safety.

Even if we accept the notion that slow vehicles are required to keep off the roadway, the statute says “as closely as practicable…” Practicable means capable of being done within the means and circumstances present. You might think that when safety is at stake, the person most at risk would be given the latitude to decide what is practicable.

But the prosecutor insisted, and the judge agreed, that the police should determine what was practicable. For the purpose of the citations, the police officers’ assessments that the shoulder was “just fine” at the time and place of the citations was the only acceptable testimony. All the testimony about the risks and conflicts to be found on that shoulder from four expert witnesses (including the prosecution’s own two expert witnesses) was for nothing.

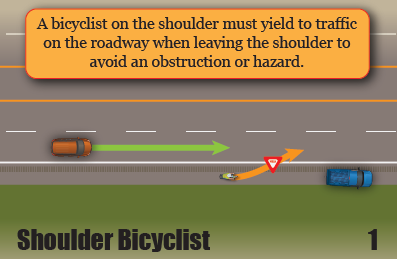

Apparently, Cherokee was expected to ride in the shoulder, only leaving it for every single immediate hazard and then returning to the shoulder, crossing the rumble strip each time after yielding and waiting for traffic to clear.

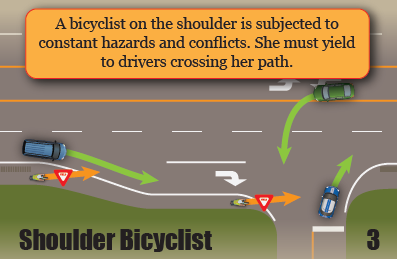

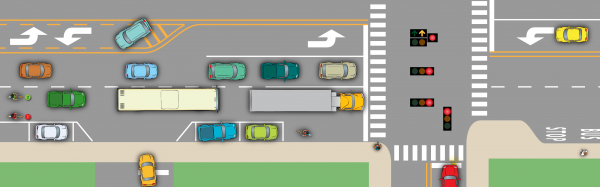

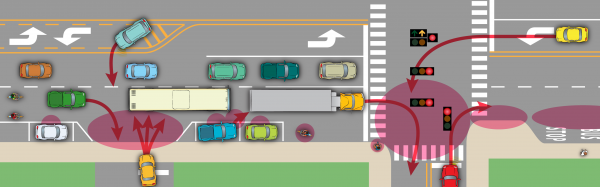

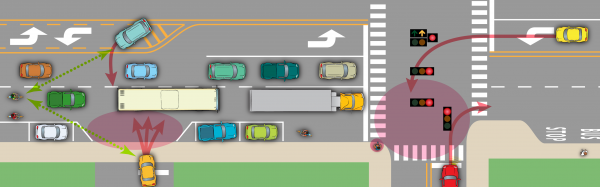

Click on the image to explore the frequent hazards and conflicts of the U.S. 27 shoulder.

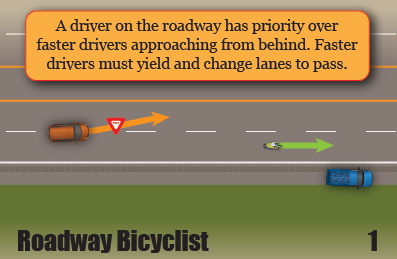

4) Operating on the shoulder is not just inconvenient, it eliminates your right-of-way and legal protection.

Right-of-Way at Intersections

KY 189.330 (10) The operator of a vehicle about to enter or cross a roadway from any place other than another roadway shall yield the right-of-way to all vehicles approaching on the roadway to be entered or crossed.

Definition of Right-of-Way

KY 189.010 (9) “Right-of-way” means the right of one (1) vehicle or pedestrian to proceed in a lawful manner in preference to another vehicle or pedestrian approaching under such circumstances of direction, speed, and proximity as to give rise to danger of collision unless one grants precedence to the other.

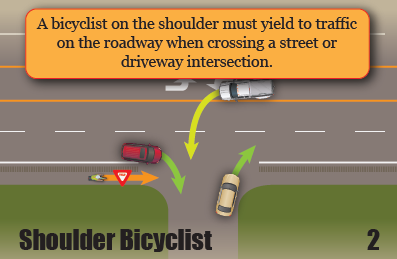

A shoulder is not like a bike lane or even a sidewalk. In most states, including Kentucky, it is an operational no man’s land (because it is not intended for vehicular operation). It is off the roadway; therefore a bicyclist using it has no right-of-way. She must yield to all traffic making conflicting movements at intersections and driveways. If someone hits her, she has no legal protection. There’s nothing practicable about operating in a space where you are both vulnerable and subservient to every vehicle on a conflicting path.

U.S. 27 is not a limited access highway. It has clusters of commercial development along it where there are frequent intersections with streets and driveways.

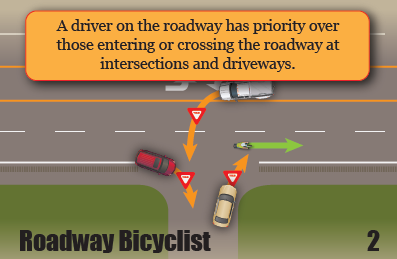

It is a fundamental rule that a roadway user has the right of first come, first served. Faster vehicles approaching from behind are required to yield and pass only when it is safe to do so. In the case of U.S. 27, there is a passing lane available for that purpose.

Every surface hazard or obstruction that necessitates leaving the shoulder requires the bicyclist to wait for traffic to clear. Moving in and out of the shoulder makes the bicyclist unpredictable. Motorists who are not paying attention, may detect her in the shoulder, then turn their attention to something else, assuming she’ll stay there.

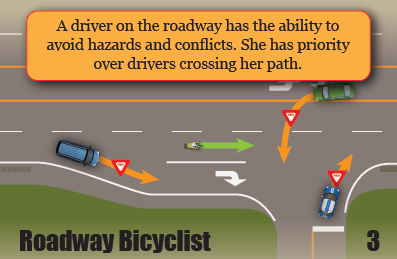

The right of first come, first served also includes other vehicles making conflicting movements. The roadway bicyclist has priority over vehicles turning left or entering the road. She also has the ability to encourage drivers who are turning right to wait and turn behind her rather than pass and turn across her path. This maneuver violates a roadway bicyclist’s right-of-way, though motorists often do it to edge-riding bicyclists).

The bicyclist on the shoulder has no right-of-way. She is not on the roadway and must yield to all traffic on the roadway, including cars turning onto or out from a cross street. A driver can legally pass her and turn right across her path. A resulting right hook crash would be the motorist’s fault if she was on the roadway, but not if she was on the shoulder. She is required to yield, even when the motorist is coming from behind her. Likewise, drivers entering from the cross street do not have to yield to her because she is not on the roadway. A driver turning left from the opposing lane not only does not have to yield to her, he may not even see her if she is hidden by passing vehicles or the heavily crowned road surface.

When right turn lanes form, the shoulder stays to the right of them, or disappears altogether. A bicycle driver in the roadway can continue in a predictable straight line, maintaining her vantage and visibility through a complex intersection.

When turn lanes divert or replace the shoulder, the bicyclist has to yield to all traffic on the roadway before she can proceed to the through lane. If she stays in the shoulder all the way to the intersection, she is even more vulnerable because she is in an unpredictable, low-visibility position. And she has no right-of-way. She must yield to all conflicting traffic.

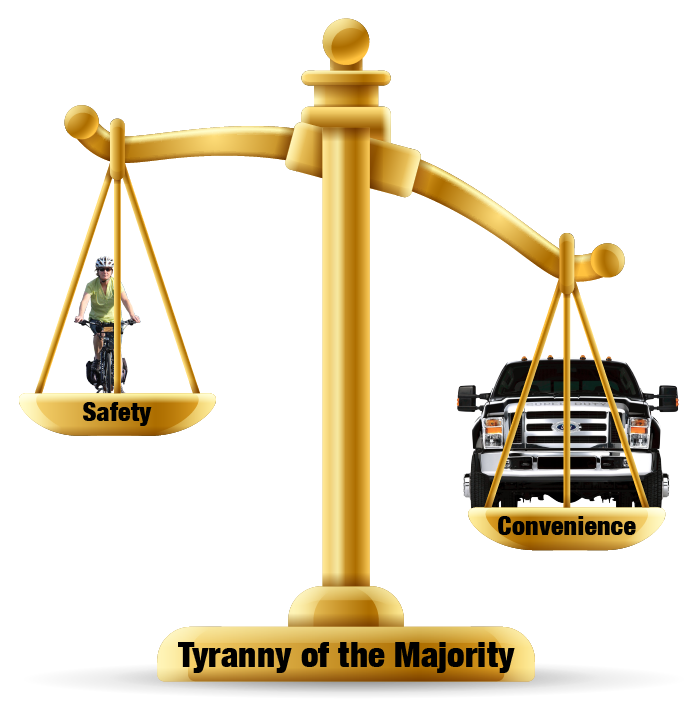

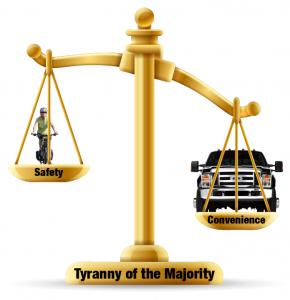

5) The scales of injustice favor the majority, no matter how absurd.

So let’s review.

Cherokee, after trying to use the shoulder and suffering its many hazards, did some research and learned that the safest, most predictable (and most efficient) way to drive her bike is to control the right lane and make herself visible and predictable.

Some motorists were incensed at having to change lanes, and possibly slow down for a few seconds, to pass her. So they abused the 911 system to complain about a bicyclist on the road.

The authorities responded by repeatedly ticketing Cherokee for careless driving. Not only that, they ignored the dangerous behavior of motorists. Once, when she called for help because a motorist was assaulting her, an officer showed up, waved the motorist away and gave her a ticket!

This case was absurd. Yet the judge sided with the prosecutor and decided that her safety is subservient to the tender convenience of motorists AND that her presence on the road endangers them. Seriously, a woman on a bicycle “inconveniences” and “endangers” motorists (in plush climate-controlled cocoons—surrounded by 4,000 pounds of steel cage, crumple zones and airbags—propelled forward at high speed by the delicate press of the driver’s toe upon a pedal). The hardship. The horror. To have to lift that toe for a few seconds to change lanes and pass a bicyclist.

Here’s how it stacks up:

The court says Cherokee must ride on a shoulder, where she has no legal right-of-way; faces numerous crash hazards and likely flat tires; must constantly stop and wait for traffic to clear in order to pass obstructions, driveways and intersections; and must endure rough, loose pavement that robs several miles per hour from her cruising speed. Beyond the safety issues, we’re talking about adding significant time (measured in fractions of an hour, not seconds) to a commute that was already over an hour… rain or shine, blistering heat or freezing cold.

All this to save motorists (in their plush climate-controlled cocoons) 20 seconds of having to drive under the speed limit, for a delay of even less than 20 seconds. Time which would easily be absorbed by the next red light or traffic jam of other motorists.

A motorist who momentarily loses less than 20 seconds can choose to step on the gas and get it back. A bicyclist who loses 20 minutes has no way to make that up.

To make this even more ridiculous, the sources of delay on this road include traffic lights, traffic congestion (of cars), motorists slowing to look for destinations, vehicles slowing to turn, vehicles entering the road, and school bus stops (which stop traffic in both lanes). But a few seconds of driving slower to pass a moving bicyclist? Well, that’s just unacceptable.

6) What kind of a society are we?

What we have here is a single mom trying to get back on her feet after escaping domestic abuse. She lost her license for financial reasons (she couldn’t afford insurance). She didn’t give up. She didn’t go on welfare. She got on a bicycle — at first, a delta trike — and rode to the only full-time job she could get. Those early commutes took her three hours each way. Three hours. She was out of shape and weighed 90 pounds more than she does today. She gutted it out. She lost weight. She got stronger. She got a faster bike. She learned how to ride safely and successfully. She was pulling herself up by her bootstraps, dammit!

Now she’s stuck. Since the trial, the police have upped the ante. A few weeks ago, they arrested her for wanton endangerment — a criminal charge — for not riding in the shoulder. And the shenanigans are getting worse. She is on parole for the violations that caused her to lose her license — driving without insurance and while her license was suspended (for failure to pay a speeding ticket in NY). Jessamine County is now trying to make her parole conditional upon not driving her bike on the roadway on U.S. 27. In other words, if she gets caught in the roadway on U.S. 27 again, she violates her parole and goes to jail.

Alternatives to U.S. 27 include adding significant distance and using a 55mph, winding, hilly, 2-lane state highway (where motorists can’t pass safely or easily) to get to U.S. 68, which is just like U.S. 27. Any alternatives to the U.S. Highways add an additional hour to a 75 minute commute into Lexington — on 2-lane roads.

She recently completed a certification course to become a Cardiac Electrocardiogram Technician and is looking for a full time job in that field. Yet, she’s basically hamstrung. There are very few jobs in Nicholasville and she has no reasonable way to get to Lexington. In addition to problems with the police, shock jocks from the local radio station have been fomenting hatred on air. As a result, militant motorists regularly go out of their way to threaten her with their vehicles. She’s even been followed by a carload of men and had to divert from her route and hide.

No one should have to live like this.

The good news is that many generous people in the bicycle driving community have been supporting Cherokee, emotionally and financially. If you would like to pitch in, you can donate to her legal fund and share this story.

To hear Cherokee’s story in her own words, listen to her interview with Diane Lees on the Outspoken Cyclist.

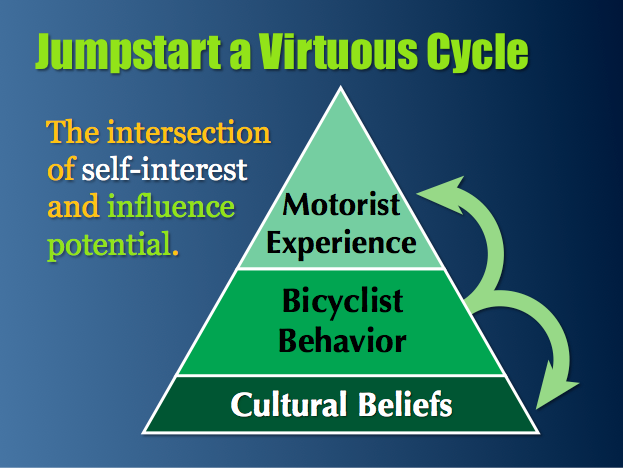

The reward for the bicyclist is tremendous: empowerment for unlimited travel. But the reward for those of us wanting to encourage bicycling is also significant. This bicyclist tells stories, too. She tells stories about all the places she goes on her bike, how much better she feels when she arrives at a destination, how easy and rewarding it is to use a bike for transportation and how courteous her fellow road users are. She’s positively connected to her community. Her enthusiasm is infectious. It inspires her friends to dust off their bikes and try a trip to the park or the store, too. If they implement her style of riding, they, too, will be empowered by success. New positive stories will begin to edge out the old negative ones.

The reward for the bicyclist is tremendous: empowerment for unlimited travel. But the reward for those of us wanting to encourage bicycling is also significant. This bicyclist tells stories, too. She tells stories about all the places she goes on her bike, how much better she feels when she arrives at a destination, how easy and rewarding it is to use a bike for transportation and how courteous her fellow road users are. She’s positively connected to her community. Her enthusiasm is infectious. It inspires her friends to dust off their bikes and try a trip to the park or the store, too. If they implement her style of riding, they, too, will be empowered by success. New positive stories will begin to edge out the old negative ones.