Vulnerability and risk. Statistics and ethics. Solutions or fixes. Top-down interventions or individual actions. These are the core issues in the long-running bike-lane (or cycle track)-versus-integration argument and in the book Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (better known for his previous book, The Black Swan). Antifragile is a long and complex read, but the author managed to summarize it while metaphorically standing on one foot: “Everything gains or loses from volatility. Fragility is what loses from volatility and uncertainty.”

Vulnerability and risk. Statistics and ethics. Solutions or fixes. Top-down interventions or individual actions. These are the core issues in the long-running bike-lane (or cycle track)-versus-integration argument and in the book Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (better known for his previous book, The Black Swan). Antifragile is a long and complex read, but the author managed to summarize it while metaphorically standing on one foot: “Everything gains or loses from volatility. Fragility is what loses from volatility and uncertainty.”

We know what fragile means; the characteristic of being at risk of serious harm or destruction through sudden and extreme shocks. We also have the term robust, which means something is mostly immune to sudden extreme shocks. Taleb noticed there are also things, people, and systems that improve with such shocks, which required the new term, antifragile. There is no hard line between fragile and antifragile; rather it is a continuum. Taleb explores this fragility to antifragility continuum throughout the book.

We bicyclists can’t make ourselves totally antifragile, to the extent that we can benefit from the volatility of traffic, but we can significantly reduce our fragility and become somewhat antifragile by learning to respond effectively to the many small violations we experience. These small violations are often indicators of the actual crash we’re trying to avoid. The close pass indicates the risk for the sideswipe. The right hook close call indicates the potential for a right hook collision. And so on. We cannot and will not become less fragile or more antifragile by putting most of the responsibility for our safety on government or motorists. The best way to achieve it is by changing our own behavior.

Butterflies are very vulnerable, but similar to bicyclists they have the options of movement which reduces their fragility; so much so that they have survived as species for millions of years.

Before we explore how to reduce our fragility as cyclists, it’s important to differentiate between fragility and vulnerability. A china cup is both vulnerable and fragile, we can reduce its vulnerability by protecting it with bubble wrap, but it remains fragile. It’s also useless when wrapped up in the bubble wrap. Butterflies are very vulnerable, but similar to bicyclists they have the options of movement (as well as coloration and chemistry) which reduces their fragility; so much so that they have survived as species for millions of years. (Options is a major theme of Antifragile.)

Bicyclists don’t collide with motorists because they’re vulnerable or slow; but mostly because they’re unpredictable or inconspicuous. (Please don’t misconstrue this as fault; predictability and conspicuity are relative, and of course some motorists are careless. But when we look at the data, it’s clear many — if not most — crashes can be avoided by improving cyclist predictability and conspicuity.) As cyclists, our vulnerability cannot be significantly reduced, but our fragility can. To reduce fragility we must reduce the volatility and uncertainty of our environment, and increase our options.

We must also bear in mind that we’re not in this by ourselves; motorists also need a more predictable environment, because they are also fragile. Yes, motorists are fragile – emotionally and economically. A collision with a cyclist is often damaging to a driver’s psyche or bank account, or both. Well-designed streets and adherence to well-reasoned rules reduce volatility and uncertainty for both cyclists and motorists. As cyclists our options are increased by enhancing (but not violating) the rules of the road with special strategies.

“A complex system, contrary to what people believe, does not require complicated systems and regulations and intricate policies. The simpler, the better. Complications lead to multiplicative chains of unanticipated effects. Because of opacity, an intervention leads to unforeseen consequences, followed by apologies about the “unforeseen” aspect of the consequences, then to another intervention to correct the secondary effects, leading to an explosive series of branching “unforeseen” responses, each one worse than the preceding one.”

—Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Rules Trump Laws (or at least they should)

Adding more rules will not solve the problem, because adding more rules adds points of failure. Instead of more rules, cyclists need more options to avoid the errors of others.

When it comes to rules it’s essential to understand how they relate to laws and to risk. Rules precede laws; they usually arise out of the culture out of experience and consensus. Laws often have political motives and biases; sometimes they uphold the rules, but other times they usurp them. When it comes to risk, particularly in traffic, we must recognize that rules which are violated become points of failure. (This is not always so with laws, because some laws are frivolous or not intended to reduce risk.)

The vast majority of traffic crashes — regardless of mode — happen because one or more parties violated one or more rules. What’s more, even if one party did not violate any rule, they often failed to take effective action to prevent it. I’m reminded of my early auto driving days as a teenager. I was driving along a collector street and another car was approaching from a side street. He was facing a stop sign and I wasn’t. From the passenger seat my dad mildly chastised me for not covering my brake. If that other driver had pulled out and caused a crash he would have clearly been at fault and received the citation, but it would have also been because I failed to take appropriate action. I would have failed to take an option available to me.

Adding more rules will not solve the problem, because adding more rules adds points of failure. Instead of more rules, cyclists need more options to avoid the errors of others. Our most important options are sufficient operating space and adequate line of sight. We can also learn ways to give motorists more options to avoid unnecessary conflicts with us.

So we need a traffic system with the fewest number of rules (not laws) possible, with street designs that support those rules, with the lowest volatility we can manage, and with the greatest options for all. This means we need a system based on what people do best and most naturally, not on what they do poorly or need to be nagged into doing. Many bicycling advocates are calling for systems that increase the failure points and reduce options both for cyclists and motorists.

The rules we have are based on the limits of human perception. Our eyes are at the fronts of our heads and we don’t have x-ray vision. They are also based on years of practical experience, first on open waters where boat captains needed to avoid collisions, and then on roads and streets when cart and carriage drivers needed to do the same. It was only when the industrial revolution came that cities got large enough and traffic got thick enough that the rules needed to be formalized into laws. Eventually traffic control devices were created to help manage the movements and reduce delays. For those who think the rules of the road were created for motor vehicles, note that less than 10% of urban traffic was motorized when William Phelps Eno wrote the first formal traffic codes for New York City in 1909. Eno thought cars were a fad and would be gone in a few years. He wrote his code for horse-drawn vehicles, bicyclists, and pedestrians, with autos, the horse-drawn and bicycles all categorized as vehicles.

The essential fairness of the rules of the road is based on the idea that all people are equal, no matter their mode. That’s why the core rule is:

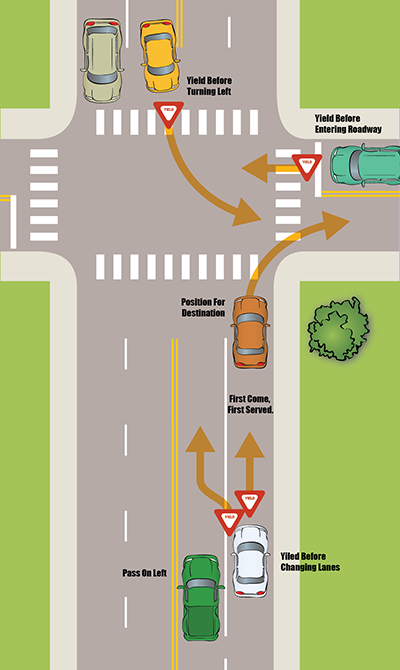

First Come, First Served. You yield to the traffic in front of you because the person ahead of you in the lane was there first. Just like at the grocery store check out. You yield when entering a roadway from a driveway because the people on the road were there first. The same goes when you get to an intersection; you yield to the person who got there before you did. When changing lanes; you yield to the person who is already in that lane. Drivers yield to pedestrians who’ve entered the crosswalk because the pedestrian was there first.

Next comes Keep Right; Pass Left. We have to all agree to keep to the same side of the roadway when going in the same direction, or else it’s chaos. And we want passing to be limited to one side to minimize the amount of scanning we need to do, and because, as I noted earlier, we don’t have x-ray vision. When you pass on the right you can be hidden from view to left-turning drivers approaching from the front.

Intersection Positioning reduces the number of conflicting movements at intersections by eliminating or minimizing converging movements, instead making all movements parallel or diverging.

Yield To the Right at Intersections. If two or more drivers arrive at an intersection at the same time, they yield to the drivers to their right. Why the right? Because motorists sit at the left side of the vehicle and the line of sight is better to the right. (Roundabouts are a special case. They’re really a set of T intersections around a circle, and with the bottom of the T yielding to the top.)

Yield To On-coming Traffic When Turning Left. The purpose of this is to minimize delay and increase certainty. And as noted above, the turning driver needs to be able to see the traffic he’s supposed to yield to.

Notice that with the exception of lane changing, drivers are to yield to people who are in front of them or to the side but still ahead. Our eyes are at the fronts of our heads. Lane changing requires a rearward scan, but lane changing is only supposed to be done mid-block, not at intersections.

In earlier times there was no rule requiring slower traffic to yield to faster traffic. That would conflict with the rule of first come, first served. Today minimum speed laws are in place in many states, but they are only intended to keep drivers of motor vehicles from unnecessarily slowing other motorized traffic. If such laws are applied to bicyclists or other non-motorized users, they are no longer about equality; they are effectively fascist, favoring the powerful over the powerless.

Seeking Order; Gaining Failure Points

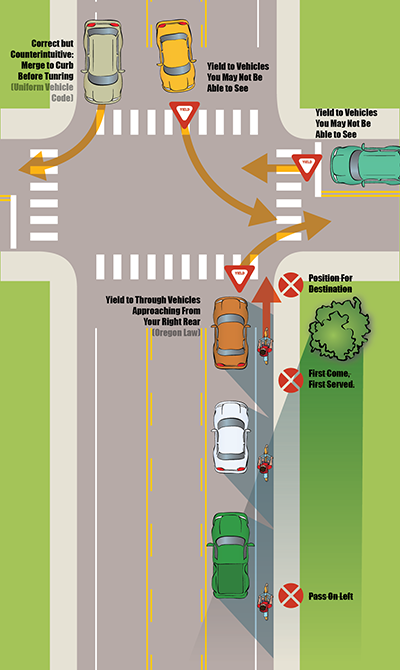

When we add a bike lane or cycle track to a street we effectively add new rules and violate some of the original rules. With such facilities, for bicyclists we now say:

Pass On the Right. The right rear section of a motor vehicle has the worst blind spots, but we expect drivers to check those spots with the same level of effectiveness as when they look forward or into their left side mirror.

Bike lanes discourage proper intersection positioning; cycle tracks often prohibit it. “When do I leave the bike lane to get into the left turn lane? Or should I just turn left directly from the bike lane?”

And for motorists we now say:

When Turning Right, Yield to Through Vehicles Approaching From Your Right Rear (your blind spot), while also scanning ahead for pedestrians in the crosswalk.

When Turning Left, Yield to Vehicles You May Not Be Able to See (because they’re moving toward you while hidden behind other stopped vehicles).

Motorists are often confused as to how to do intersection positioning. “Do I move all the way to the curb as I normally do, or do I stay fully in my current lane?”

So we have added new rules, which means new points of failure. What’s more, these rules are more difficult to obey because they require motorists to look back when they also need to be looking forward, and they require both cyclists and motorists be able to see through stopped vehicles. None of these new rules, or the bikeways that necessitate them, eliminate the need for adherence to any of the original rules, or eliminate the crashes caused by the violations of those rules.

Types of bicyclists and types of bicyclist behaviors.

Bicycle planners are fond of systems that attempt to categorize bicyclists into “types.” The most commonly used type system uses “A” for “experienced” adults, “B” for “novice” adults, and “C” for children. The problem with this system is it assumes certain types of behaviors and preferences for each group, but with no data to support those assumptions. A far better approach is to categorize basic types of behaviors. Some behaviors are more successful at mitigating conflicts and crashes, and some are less successful. Whether a cyclist is a 40 year old man on a $2,000 road bike or a 12 year old girl on a bike from Target is beside the point. Successful behaviors work for everyone. Unsuccessful behaviors fail for everyone. (The presumption that successful bicycle driver behavior is not achievable by novice adults or by children in an appropriate environment is demonstrably false. It’s been done.)

On the other hand, the basic behavior types are driver, edge and pedestrian. Pedestrian behavior is bicycling on a sidewalk, a sidepath, or on the roadway against traffic. Edge behavior is cycling close to the roadway edge with the flow of traffic. Driver behavior is using the roadway in the same manner as any other driver of a slower vehicle, usually in the center of a lane. It’s not a matter of whether a behavior is “right” or “wrong,” but whether it’s successful or unsuccessful for a given type of street and situation. The well-trained cyclist understands the pros and cons for each behavior.

For more about the bicyclist behavior spectrum, see Bicyclist Behaviors & Crash Risk

For some strange reason, the opinions of the untrained and less experienced cyclists are held in higher regard than those of the trained and experienced ones. I know of no other activity in which that is the case.

A bicyclist whose default behavior is driver sees a bike lane or cycle track as adding volatility and limiting options. A bicyclist whose default behavior is edge or pedestrian sees a bike lane or cycle track as reducing volatility and increasing options. This is partly because he or she has little or no experience using driver behavior, and partly due to what the majority bicycling culture is saying. It also creates some cognitive dissonance on the part of the edge or pedestrian rider, because he still experiences conflicts while in the bike lane or cycle track.

For some strange reason, the opinions of the untrained and less experienced cyclists are held in higher regard than those of the trained and experienced ones. I know of no other activity in which that is the case.

“What can we say about people who studiously avoid learning from the mistakes of others?” — Taleb

There are better ways to attempt to reduce volatility and improve options that don’t involve violation of the rules of vehicular movement. The best is to reduce motor vehicle speeds in urban and suburban areas, and to limit the number of multi-lane arterials. The faster we travel the poorer our ability to track multiple conflicts and the more distance we need to react to them. Crash data from Florida shows that crash rates for all road users increase significantly when roads are widened from four lanes to six.

We can accept the superiority of bicycle driver behavior over edge and pedestrian behavior by the simple observation that people who effectively learn bicycle driving do not revert to the other behaviors as their default; driving becomes their default because it clearly works better for them (though bicycle drivers will on occasion use edge or pedestrian behavior when it serves a specific purpose.)

“Suckers try to win the argument; non-suckers try to win.”

– Taleb

This bike-lane-versus-integration argument has been running for 30 years at a stalemate, and statistically speaking it’s unwinnable. The argument is in essence: overtaking crashes versus other crashes. The experienced and trained bicycle driver sees the risk of the overtaking motorist as exceptionally low and the risks of turning and crossing conflicts as significantly higher. (Overtaking crashes account for no more than 10% of urban and suburban crashes, while most of the rest involve turning and crossing conflicts.) Based on direct, real world experience they see bikeways that keep cyclists along the edge of the road as increasing their risk for turning and crossing conflicts. Virtually all cyclists who predominantly use driver behavior were once edge or pedestrian riders, so they understand the difference in effectiveness based on real world experience.

Cyclists who predominantly use edge or pedestrian behavior have little to no experience with bicycle driving behavior, so they are unable to compare the effectiveness for themselves.

Advocates of bike lanes, cycle tracks and sidepaths see the risk of overtaking motorists as unacceptably high and believe the turning and crossing conflicts that bikeways create can be mitigated with better design and motorist training and enforcement. They also tie the tenuous safety benefit of bikeways to the desire to get more people on bikes, making the equally tenuous claim that getting more people on bikes will reduce the crash rate (but not the crash numbers). Cyclists who predominantly use edge or pedestrian behavior have little to no experience with bicycle driving behavior, so they are unable to compare the effectiveness for themselves.

If you’re going to trade off one risk for another, you have to first know which risk is greater. Statistically speaking, that means knowing the absolute risk in a measure such as crashes per mile or per hour of exposure. What’s more, you need to know how those risks change with different environments. For example, the risks of turning and crossing conflicts are relatively low on a high-speed rural road with few cross streets and driveways, but one could reasonably expect overtaking crashes to be a potential problem. Conversely, on a low-speed downtown street with many driveways and cross streets, turning and crossing conflicts are a significant concern and overtaking crashes are exceptionally low. Lane control greatly reduces the predominant type of overtaking crash, the sideswipe, in which motorists attempt to squeeze past cyclists within the lane. Therefor, the only type overtaking crash that lane control might not mitigate is the type in which the motorist is so seriously impaired or distracted that he or she does not see the cyclist directly ahead. Such crashes in the urban context are so rare they could be compared to being struck by lightning.

In order to measure the risk for a particular type of crash and how it might change by the type of street, you need to measure quite a few variables, and be confident you’ve measured them accurately. To put this to use, you also need to create a sound mathematical model that reliably predicts the risk for different situations.

Let’s take one type of crash – the right-hook – as an example. In order to predict how many right-hook conflicts per mile or per hour cyclists would expect if they are traveling along the edge of the roadway, we need to know:

- How many cyclists travel along the street

- How many motorists travel along the street

- The numbers of intersections and driveways (minus the ones where there is a dedicated right turn only lane)

- The number of signalized intersections

- How many motorists make right turns at each intersection

- The relative average speeds of the motorists and bicyclists (the closer the relative speeds, the higher the likelihood a cyclist will be in the blind spot of a motorist who’s turning right)

- The percentage of motorists who check their right side blind-spots before turning right

And there may be other factors I haven’t thought of. Other turning and crossing conflicts, such as left-crosses and drive-outs, would have their own sets of necessary factors.

Similarly, to measure the absolute risk of overtaking crashes for cyclists who control their lanes we need to know:

- How many cyclists travel along the street

- How many motorists travel along the street

- The relative average speeds of the motorists and bicyclists

- The percentage of motorists who are distracted, and how long on-average their attention leaves the road

- The percentages of motorists who are intoxicated and sleep-deprived

Also at issue is the relative injury severity of the two (or more) crash types. Once again, overtaking crashes might have high risk of death or serious injury on a rural road, but not on an urban street, while right hooks involving large trucks in low-speed environments have very high fatality risk. These rates are also unknown and difficult to measure.

If you cannot predict which risk is greater, then you cannot ethically restrict a person’s options for limiting their risk based on their own real world experience.

This should explain what I mean when I say the argument is unwinnable, as least from a statistical analysis standpoint. One side can argue that the overtaking risk is higher, but cannot prove it (at least not to anyone looking at the data objectively), and the same is usually true the other way. If you cannot predict which risk is greater, then you cannot ethically restrict a person’s options for limiting their risk based on their own real world experience.

A cyclist who is concerned more about overtaking motorists than about turning or crossing conflicts always has the option of biking along the roadway edge, and often has the option of using a sidewalk. He or she also has the option of controlling the lane, but either chooses not to utilize it or thinks that option is illegal or unsafe. If the lanes on an existing road are narrow and the road has no sidewalks, one could argue that options are limited for this cyclist. He has two options, neither of which he likes. But note that at this point no action has been taken by anyone in authority to change the available options. We could make the lanes wider or add sidewalks; this adds options for this cyclist, and he may or may not prefer these options.

A cyclist who is concerned more about turning and crossing conflicts has the same options as the first cyclist, and will normally choose driver behavior – until a bike lane or cycle track is provided. Now an option has been removed or somewhat restricted. Whether or not there’s a law restricting the bicyclist to the bikeway, the cyclist who avoids the bike lane in order to avoid turning and crossing conflicts gets punished, either socially (through motorist harassment) or legally (through police action). What’s more, the punishment is being doled out to the trained and experienced cyclist who is attempting to avoid a well-document conflict.

A bike lane or a cycle track is a traffic control device. According to the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices:

“The purpose of traffic control devices, as well as the principles for their use, is to promote highway safety and efficiency by providing for the orderly movement of all road users on streets, highways, bikeways, and private roads open to public travel throughout the Nation.

Traffic control devices notify road users of regulations and provide warning and guidance needed for the uniform and efficient operation of all elements of the traffic stream in a manner intended to minimize the occurrences of crashes.”

Notice it doesn’t say “to make people feel comfortable and encourage them to ride bikes.” Nor does it say “support common behaviors” such as bicyclists passing on the right or riding against traffic. Are there any other traffic control devices that expert drivers believe add unnecessarily to volatility, reduce predictability, and eliminate defensive driving options?

There may be areas in which the downsides of a bikeway are very minimal and the upside is significant, such as sufficiently wide bike lanes on high-speed suburban roads, or sidepaths along high-speed rural highways. But a blanket “put in a bike lane” attitude is not a wise strategy.

Laws that eliminate or restrict defensive driving options are even worse. Bicyclists are the only vehicle drivers who (at least in most states) are put in the default position of sharing a lane side-by-side with much larger and faster vehicles. By controlling a lane we get the kind of passing clearance and protection from turning and crossing conflicts that we want, but lane control is framed in our statutes as the exceptional option, not the default option.

How Much Risk Reduction Do You Want?

Would you prefer a 40% reduction or as close to 100% as possible? Published studies comparing streets with and without bikeways vary quite a bit with their claims of crash risk reduction. For the sake of argument, 40% is fair starting point. (I’ll get to the validity of those claims in a bit.) I’ve no doubt you’d rather take the close-to-100% option if it seemed reasonable.

If you go through a Goal Zero process and ignore the most effective strategies for reasons like “people aren’t interested in that” (a common argument against expecting people to seek cycling education), you’re really saying “a 40% reduction is good enough.”

The gold standard of safety programs is the “Goal Zero” approach. With Goal Zero you look at every angle of the system, every point of failure, and strive to understand it as clearly as you can. Then you analyze all the potential strategies to reduce or eliminate those points of failure and determine which strategies are most effective. In bicyclist safety circles that’s called the “3E” approach: engineering, education and enforcement. Enforcement is just trying to ensure people do what they’ve been taught. Too often “education” itself is presented as a countermeasure, but it’s really not. Education is a way to demonstrate to people the types of behaviors that are most effective. It’s the behaviors that are the real crash countermeasures. They don’t work unless the cyclist (or motorist) uses them.

If you go through a Goal Zero process and ignore the most effective strategies for reasons like “people aren’t interested in that” (a common argument against expecting people to seek cycling education), you’re really saying “a 40% reduction is good enough.” Well-designed bicyclist training programs (such as CyclingSavvy) take the Goal Zero approach by addressing each type of conflict and using the most effective countermeasure, not the most popular one.

But I was being charitable to those bikeway studies a few paragraphs back. Their claims of crash rate reductions are highly suspect due to poor methodologies. None of the studies address cyclist or motorist behaviors. They simply look at all the crashes before and after the installation, or compare crashes on streets with and without bikeways. In order for such comparisons to be valid you have to screen out crashes that wouldn’t have been affected by the bikeway presence, such as someone running a red light or a stop sign, or a cyclist entering the roadway from a driveway, or one out at night without lights.

These studies don’t compare bikeway travel to bicycle driver behavior; they compare bikeway travel to edge and pedestrian behavior without bikeways, because those are the dominant bicycling behaviors. The full range of behavioral strategies has therefore not been studied.

Worse still, some studies have made comparisons between bikeway streets and non-bikeway streets without keeping the other street characteristics consistent. For example, in the Lusk, Furth et al study of Montreal cycle tracks, one-way, one-lane residential streets with cycle tracks were compared to two-way, four-lane commercial streets without bikeways. They also ignored crashes that might have been relevant, but we can’t tell from their paper. (They also omitted a cycle track section that was already known for a high crash rate.) Critiques of that study can be found here and here.

We also have to consider the unintended consequences scenario. If we build a bikeway that is generally believed to be safe, the proponents say, more people will come out to bike. This may well be true, but will those new cyclists keep only to the bikeways? Of course not. And will they seek out training? Not until we get serious about it as a culture. So we will have more cyclists out on all of our streets, but they are doing so with the less successful edge and pedestrian behaviors. The bikeway designs might partly mitigate the failures of edge and pedestrian behavior, but of course not on the streets without the bikeways. So it’s completely predictable that crashes would go up on non-bikeway streets compared to the bikeway streets because we’ve invited a bunch of untrained people into situations they don’t understand, and have reinforced the types of behaviors that get them into trouble to begin with. But the pro-bikeway study authors take this as validation.

The things we don’t measure are often as important, or more important, than the things we do.

“It would be nice if all of the data which sociologists require could be enumerated because then we could run them through IBM machines and draw charts as the economists do. However, not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”

—William Bruce Cameron, “Informal Sociology: A Casual Introduction to Sociological Thinking”

Inhibiting people from learning better strategies is also unethical. How does a novice ever learn to reduce his own risks if training is dismissed as irrelevant or impractical and the infrastructure discourages the more successful behavior?

Bicyclists get hit by motorists while traveling in bikeways. They get rear-ended, right-hooked, and left-crossed. They also get hit by motorists driving out from driveways and cross streets. There are also crashes involving wrong-way cyclists in bike lanes. Yes, of course, these crashes also happen to cyclists who are not in bike lanes, but no-one has solid data showing they are less likely with a bike lane. It’s unethical to limit an individual’s attempts to reduce their risk if you don’t have strong certainty that you have a better strategy. Bicycle drivers know from direct real world experience – which includes all the pertinent factors, just not in the form of quantifiable data – that they have far fewer close calls involving such conflict types when they are controlling a lane than when they are in a bike lane or otherwise along the edge.

Inhibiting people from learning better strategies is also unethical. How does a novice ever learn to reduce his own risks if training is dismissed as irrelevant or impractical and the infrastructure discourages the more successful behavior? Some years ago I met a man who’d spent quite a few years living in The Netherlands. Like so many, he loved their bikeway system and raved about it to me. I didn’t argue with him about it, but just reminded him that here in Orlando you have to know how to handle yourself on roads without bikeways. He assured me he knew how to bike safely in mixed traffic. Each time I’ve seen him since he’s been cycling on a sidewalk.

We could liken bike lanes and cycle tracks to placebos. Even placebos have some positive health effect, but we would never give a placebo when the real drug was much more effective. Vaccines on the other hand work very well. They strengthen the immune system rather than attack the malady directly. Training is a vaccine; it shows the cyclist how to address the most common problems wherever she goes — not just where the government has installed a special treatment — and no-one is misleading her into thinking some other agent will handle her problems for her.

A Robust System

While we can’t make individual cyclists robust or entirely antifragile, we can do it for our overall traffic system. Our traffic system is inherently based on cooperation, but too many people are trying to treat it as though it’s a competitive one. Whether it’s the motorists-as-wild-beasts theme, the media pumping up the us-versus-them angle, or some bicycle advocates with their us-versus-them brand of activism, they are all making the system unbalanced and less effective by bolstering the competitive mentality.

Cooperation is what makes our traffic system robust. It’s what gives it safety redundancy; it’s what makes its users smarter and more effective; it’s what makes traffic flow smoothly; it’s what makes us focus on our own responsibility rather than everyone else’s; it’s what rewards successful behaviors.

Confusion (such as when the system is made too complex) confounds cooperation and feeds competition.

Cooperation is strongest within species and cultures, not between them. So “pedestrians and bicyclists as endangered species” and “bike culture versus car culture” are harmful analogies. We are all one species: homo sapiens. We are genetically and culturally guided to protect the vulnerable of our own species. Protection of the vulnerable is a far more effective driver of human cooperation than the law. A motorist who expects to see bicyclists on all roads (except freeways) and on all parts of the roadway will be more diligent in looking for cyclists than one who expects them to only be on paths or bike lanes.

If we want an antifragile system then, we need three key ingredients: simple rules, cooperation and vulnerability.

Simpler rules increase predictability.

Vulnerability combined with predictability increases cooperation.

And cooperation strengthens the rules.

It’s a virtuous cycle.

“You get pseudo-order when you seek order; you only get a measure of order and control when you embrace randomness.”

—Taleb

I somewhat doubt that most biker’s fear crashes. Many of us instead are afraid of bullies in motor vehicles. So we ride on the edge or on the sidewalk and demand separated facilities in order to stay away from bullies. These bikers are especially resistant to training, I think, because their problem is not safe roadway interaction, it’s just bully avoidance.

Mighk knocks the ball out of the park with another great essay. I’m thinking of ways to share it. Especially insightful is the idea that adding infrastructure reduces options, just the opposite of what three-hundred-million Americans think.

The idea that options are reduced is based on the notion that, once segregated infrastructure is built, the bullies come out in force, if I choose to cycle in the road and don’t stay on the side path.

Side paths enable the bullies, few as they are in practice.

I’m remembering why I edge rode (before reading John Forester’s Effective Cycling in 1977). It wasn’t bullies, it was fear. (Your experience may, certainly, be different depending on local customs and attitudes). I knew that I was taking a risk but I thought I was avoiding a greater risk. I fatalistically accepted the risk, and felt entitlement for using an environmentally friendly transportation mode.

My transition was almost immediate on reading the book. Not only was it clearly safer to use lane control and destination positioning, it was more convenient. Also for the motorists. My self justification changed to simple good citizenship.

Mighk,

One thing to point out is that there is plenty of crash experience in Europe and the US where the crossing crash to overtaking crash rates consistently show between a 4 to 1 and 5 to 1 predominance of crossing (intersection) to midblock (crashes). And in addition, many overtaking crashes are for cyclists at the road edge or on a shoulder, so it is not even clear that choosing edge behavior necessarily reduces overtaking crashes, but certainly invites crossing crashes at driveways and intersections.

I didn’t mean that there are a lot of bullies but that the fear of bullies seems to keep some, perhaps many, people from proper driving.

Very true Dan. The bikeway promoters then shift to the argument that overtakings result in more serious injuries, which conflates rural with urban, night-time with daytime … and the game of whack-a-mole continues.

Mighk, this really ties a lot of important ideas together and will give me something to think about for quite some time.

However, concerning the added failure points of bike lanes in your illustration, isn’t it possible to avoid or at least significantly mitigate them with non-edge bike lanes the like the right-buffered bike lane with the intersection treatments shown in the infographics on this website? Wouldn’t that be the best solution where there is room for such a facilitiy?

https://iamtraffic.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/widthsx2_short_preferential.png

Gary, buffering the bike lane doesn’t solve the screened left cross. I’m seeing quite a few of those in metro Orlando.

Mighk, I don’t see why there would be any more risk for screened left cross than with the cyclist controlling the right lane of a four-lane road. The buffer drops before the intersection providing the same geometry as a four-lane intersection.

Very good article indeed. Two very minor nitpicks:

1. The article says motorists are fragile emotionally and economically, but let’s not forget that they are also just as physically fragile as cyclists: their bodies are exactly the same as ours. Also, the vast majority of deaths on the road are motorist deaths. Also, statistics indicate that, over short distances, cyclists are LESS likely to be injured or killed than motorists. Motorized vehicle speeds combined with overly-liberal speed limits and other factors result in a situation in which safety features are often rendered ineffective, placing motorists at even greater levels of vulnerability than cyclists and making them effectively more fragile, despite the appearance of resilience and strength that their steel cages, crumple zones and airbags give them.

I think we run the risk of falling into the trap of making ourselves seem weaker than we are if we ignore motorists’ physical fragility. The cyclist weakness argument is at the core of many fearful cyclists’ unwillingness to adopt integrated cycling practices.

2. The article seems to tacitly accept the segregated facility advocate position that the “risk of overtaking motorists” (the risk of a rear-end collision) applies mainly to cyclists who take a central position in the lane, yet no study I’ve ever seen confirms this. It is my belief that this tenet of the segregationist creed is fundamentally flawed. I believe very strongly that, if this issue were to be studied carefully, we would find that edge-riders, and NOT bicycle ‘drivers’, are more at risk from this type of collision.

Bicycle ‘driving’ may REDUCES risk from overtaking motorists. Ignoring this effectively concedes this aspect of the argument.

When my dad taught me to drive he said ” You have the Right of Way, when the other person gives it to you.”

Followed by, ” Its your choice if you want to be Dead Right”.

Bill, what you’ve written is fearmongering nonsense – it’s the sort of rubbish that gets written by those who don’t know the rules of the road and who don’t care to learn them.

Priority (commonly known as ‘right of way’) is not subservient to personal whim. In every circumstance on the road there is someone who has priority and others who do not. There are rules that determine priority and the law REQUIRES that we follow those rules. If we do not have priority we have a duty to yield. Similarly, if we have priority, we have a duty to move as the law requires – carefully yes, but still we must take priority, because we are required to do so.

Yielding priority when we have it is inherently dangerous, because it creates uncertainty and unpredictability on the road. Your dad was wrong. You must not always yield until someone else yields to you – you must know when to yield and when to go, based on the rules and laws. If you yield priority when you should take it, you make accidents more likely.

As for the idea that you can be ‘dead right’, yes, that is certainly the case, which is why all movements on the road should be done with care. Even so, accidents happen, but we take that chance every time we go out into the road. Life contains a particle of risk, but that doesn’t mean we should start making up our own rules for the road – that makes life more risky, not less so.

Ian you are right on both points. I was trying to keep the length down and not get too deep into the details. Thanks.

Right-of-Way is merely — nothing more than, nothing less than — a set of dance instructions that specify who will do what and when during participation in traffic, which is the event that CyclingSavvy calls the “dance you must lead.” Yielding is the key dance move, but it’s important to keep in mind that “yield” is not a synonym for “surrender.”

As Ian explains, it’s just as unsafe for a person to surrender his Right-of-Way as it is for a person to claim a Right-of-Way that is not his.

This is why it’s not safe for the Sensitive, New-Age Motorist to surrender his Right-of-Way to “the nice biker” at a four-way stop. Rules suspended. Chaos reigns. Dancers, not knowing what to do, bump into each other. It’s also why it’s unsafe for a driver to “doze off” at an intersection, to lose his focus, and to wait to see what happens next. Everyone needs to pay attention and to be ready to act: The person who has the Right-of-Way must move next, else the system quickly cascades into chaos.

Right-of-Way is an unfortunate name for a set of rules that have nothing to do with “rights” as the term is more-frequently used in, for example, the expressions “the right to remain silent” or “the right to keep and bear arms” or “the right to a fair trial.”

Right-of-Way is not a list of rights. It is merely a detailed but simple way of deciding who will yield in a given situation in traffic. For example, one must not enter a lane of traffic without yielding to drivers who are already in that lane: First-Come, First-Serve Rule. Since within this system, everyone eventually gets to be first, the system is equitable and fair, and because it is equitable and fair, it also works.

“It Works!” — The Ultimate American Value.

“You may be right, but you’ll be dead right,” is an interesting one, because “Dead Right” is an apparent oxymoron on a par with “British Humor” and “Wildlife Management.” The Right Thing is that you don’t end up dead.

The opposite of “Dead Right” — “Alive Wrong” — would be a good label for a failed suicide, I suppose.

“You may be right, but you’ll be dead right” also fits into a category with other commonsensical, non-actionable advice on a par with “Ride safe and have fun,” the club favorite here, and “Watch out for cars; don’t get hit,” the favorite of moms everywhere. And the ever-popular “Stay out of the way of cars,” and “Cars weigh more than bikes.”

Examples of non-commonsensical, actionable advice — things that one could do (take action on) but that one seldom hears uttered — include “Ride in the center of a narrow lane”; and “Yield to traffic before entering a lane of traffic”; and “Use hand signals when preparing to turn or stop.”

These last three are rather dull and lack the poetic charm of “You may be right, but you’ll be dead right,” and lacking in poeticality, they are harder to remember, but they do have two huge advantages: They can be acted upon, and if one does act on them, they can positively affect one’s safety. One can be “right” in the sense of being less-likely to be dead.

Regarding British humor being an oxymoron, all I have to say is this: top quality British comedy shows don’t need a laugh track to tell the audience where the joke is. American comedy shows all use a laugh track.

Install Strict Liability & a lot of these alleged problems disappear. That is why the cycling nations of Europe enacted it years ago

The conflicts and crashes may be reduced through the enaction of such laws, but they most certainly do not “disappear.” Believing the enactment of a law eliminates unsafe behavior is naive in the extreme. How long have we had laws against running red lights? (Since traffic signals were invented.) How long have we had motorists (and cyclists) violating red lights? (Same answer.)

Ian: I added some text in the risk concern comparison section to address the lane control and overtaking issue.

There are something like 500,000 cycling injuries in America each year, and about 700 of them are fatal.

There are also about 300,000,000 real and potential cyclists in America.

Suppose that you were Chairperson of the House Ways and Means Committee, and suppose that you were getting ready to appropriate, say three-hundred-million dollars a year for the foreseeable future to reduce the injuries. And suppose that you could choose only ONE avenue through which to outlay the money: Education, Infrastructure, New Traffic Laws (e.g., three-foot passing laws; mandatory helmet laws), Better Enforcement of Existing Laws, Stricter Liability Requirements, or Other (I’m running out of ideas!).

Which would you choose? Which ONE avenue do you believe would return the greatest reduction of injuries per dollar spent? (“You” is anyone reading this.)

I tend to think money is best spent on education. In my experience, education of road users is appalling and the potential for improvement is both great and could be done inexpensively using mass media campaigns.

I would not focus on the other options because in my opinion, infrastructure is generally good, traffic laws are adequate, enforcement is poor but improving it may prove costly, and stricter liability requirements would be tough to implement.

What Robert said!