This is the first in a series of posts highlighting the challenges for encouraging bicycling in America.

Part 1: Origin & Influence of Our Stories

The stories we tell are a product of the experiences we have. Our experiences are the product of our choices and behavior. There’s a saying popular among pilots: “Good judgment comes from experience. Unfortunately, the experience usually comes from bad judgment.” In bicycling, the journey to good judgment is complicated by inhibiting beliefs and social norms.

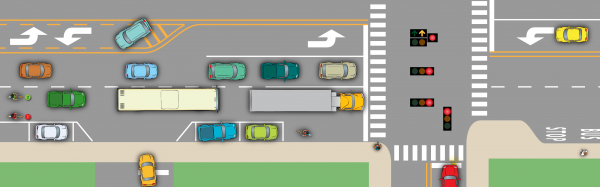

Test Your Recognition of Potential Conflict

The image below is similar to one we use in the CyclingSavvy course. It’s a participation exercise to engage students in spotting conflicts they have just learned about in a previous section on crash causes and prevention. Test yourself in Tab 1. Tab 2 shows the potential conflicts faced by the cyclist in red (practicing edge behavior). Tab 3 shows the potential conflicts faced by the cyclist in green (practicing driver behavior).

[tabs slidertype=”top tabs”] [tabcontainer] [tabtext]Spot the Potential Conflicts[/tabtext] [tabtext]Edge Bicyclist[/tabtext] [tabtext]Driver Bicyclist[/tabtext][/tabcontainer] [tabcontent] [tab]

click images to enlarge

Count the conflicts faced by each of the two cyclists on the left side of the picture, then click the tabs above or below for highlighted conflicts and explanations.

[/tab] [tab]

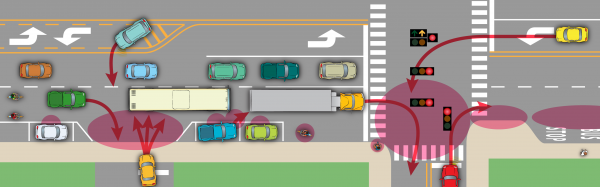

There are numerous mid-block conflicts:

- Door zone: every parked car is a potential dooring conflict.

- Parking pull-out: every parked car has the potential to pull out when there is a gap in traffic. The edge-riding bicyclist may be in the drivers’ blind spots.

- There is a wrong-way bicyclist weaving in and out of parking spaces. He will be a head-on conflict for an edge-riding bicyclist.

- Beyond the intersection is a pinch point where the lane is too narrow for a bicyclist and a truck or bus to fit.

- Buses entering or leaving the bus stop are a problem for the bicyclist. He is likely to be in the blind spot of the bus drivers.

The driveway offers several crossing conflicts:

- The driver of the green truck could suddenly decide to turn right into the driveway.

- The driver of the yellow car may pull out and go in any direction—if he is working a gap, to turn left or get to the left-turn lane, he will be focused on the cars and unlikely to look at the edge of the road.

- The driver of the turquoise SUV is looking for a gap to make a left turn. The green truck screens the edge bicyclist from view.

The main intersection offers several crossing conflicts:

- The pedestrian may try to cross before the light changes. He will step into the edge of the lane before proceeding.

- The tractor trailer might turn right. It will look as if it is going straight because the driver needs to steer wide. He will need to navigate the turn slowly to avoid off-tracking over the sidewalk, allowing plenty of time for the edge-riding bicyclist to enter his blind spot.

- The driver of the red truck wants to turn right on red. He may jump the light, or be looking for a gap.

- The driver of the yellow car is planning to turn left. If the red cyclist is fast and that driver runs the stale yellow, they would be on a collision course and invisible to one another.

The frequency of potential conflicts on the edge requires managing multiple threats at once… and that’s if the bicyclist even recognizes the conflict potential. Many bicyclists who ride this way don’t. They suffer constant close calls. Their trips are full of unpleasant surprises because they are frequently invisible or irrelevant to other drivers. But unlike the pilot, most don’t have the training to recognize the root cause of their bad experiences or how to eliminate them.

[/tab] [tab]

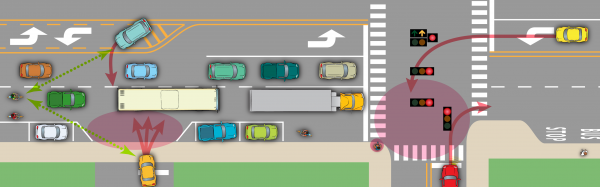

The green bicyclist is clear of all of the mid-block edge conflicts. She is well outside the door zone. She’s easily seen by drivers pulling out of parking spaces. She also has plenty of space to avoid them. She won’t be bothered by the wrong-way bicyclist.

Drivers of all vehicles face potential conflicts at driveways and intersections. Like a motorcycle driver, this bicyclist has positioned herself for the best vantage and visibility—she can see conflicting drivers and they can see her. She simply needs to be aware of a potential moving screen: cars to her left screening her view of left-turning drivers.

With only a few potential conflicts to monitor, the driver bicyclist has a virtually stress-free ride. She prevents most right-of-way incursions just by being visible and relevant. She knows where to place her attention and the value of communicating with others. She encounters almost no surprises.

[/tab] [/tabcontent] [tabcontainer] [tabtext]Spot the Potential Conflicts[/tabtext] [tabtext]Edge Bicyclist[/tabtext] [tabtext]Driver Bicyclist[/tabtext][/tabcontainer][/tabs]

To learn more about the types of bicyclist behavior and how they influence crash risk, see Bicyclist Behaviors & Crash Risk in the Engineering section. In this post, we will explore the cultural influences and social implications of bicyclist behavior.

The Distorted Lens

The two bicyclists above not only have vastly different personal experiences, but the people with whom they interact also have a dramatically different experiences. For better or worse, we are all ambassadors. A close call or crash involves two people: the bicyclist and the motorist. They both leave the encounter affected by it. They also influence their families, friends and co-workers with the stories they tell about bicycling and bicyclists. Those stories become the lens through which the people around them view bicycling.

Anyone who has spent any time on bike blogs, forums and comment sections has encountered many, many “motorists are idiots” stories. These are predominantly stories of the unsuccessful bicyclist practicing edge or pedestrian behavior. He gets buzzed and cut off frequently. He wants new laws requiring motorists to move over, or yield to him when he’s passing on their right. He loves PSA campaigns that tell motorists to look for bicyclists, but it hasn’t occurred to him that there are things he can do better. He’s riding the way he believes he is expected to. Good thing he’s tough. Bicycling on the edge of the road is only for the fearless, fast and thick-skinned warrior.

Under the bravado is a disempowered, unsuccessful road user who needs other people to change so bicycling can be less frustrating. Most of us know this guy, or we’ve been him. He has been the face of American bicycling for decades.

If he never learns there’s a better way, he gives up and goes back to driving a car.

The Stories of the Unsuccessful Bicyclist

I’m a second class citizen.

I’m at the mercy of others.

Most motorists are careless and mean.

Bicycling is difficult and frustrating and won’t be safe until other people change and we have special facilities.

The majority of American bicyclists are locked into this cycle of conflict and frustration. In fact, the beliefs of our culture are designed to hold them there.

Get Out of the Way or Be Killed

Throughout history, dominant cultures have held their norms in place with stories, symbols and ideas designed to discourage deviation. This is called control mythology. It is insidiously woven into the culture so that it is not recognized as anything other than “the way it is and always has been”—an unchangeable fact of life. It is the underpinning of beliefs, customs and laws. It is the root cause of many intractable problems throughout the world. Tragically, it is often held in place most strongly by the subordinates it is intended to suppress.

The plight of the unsuccessful bicyclist is the product of the control mythology by which motordom, and its culture of speed, came to dominate our public roadways. Our current beliefs about the road date back only to the 1920s. As the motorcar entered our cities, it quickly ran up against the dominant pedestrian culture—a culture that had believed for thousands of years that streets were for people. The speed of the motorcar was incompatible with that culture’s customary use of the streets for socializing, commerce and movement of people and goods by human and animal power. The resulting clash—and death count—threatened to curtail the usefulness of the motorcar. So began a deliberate effort by a wealthy minority of motoring interests to reframe the purpose and preferred users of our streets.

The Great Reframing resulted in the creation of a control mythology designed to clear the roads of anything that slows motorized traffic. To control by fear, it changed the perception of cars from vehicles being driven by people who are responsible for safe and competent operation into traffic—a faceless force of nature which must be avoided. That alone has had repercussions for safety, civility and justice for all road users. The reframing dissociated higher speed from greater responsibility, foisting upon us the utterly false belief that it is dangerous to be slow. But fear alone isn’t enough. Being slow and in the way is also socially unacceptable. Thus, if you shake off the imposed irrational fear, your peers will try to keep you in your place.

After almost 100 years, the beliefs that inhibit successful behavior have been accepted unquestioningly by most people. The forces that deliberately reframed our roads are long gone. Tradition now holds their legacy in place. Worst of all, the mythology is now so thoroughly perpetuated by the stories of unsuccessful bicyclists, the status quo would seem to have little to fear.

We Shall Overcome

Understanding these beliefs is essential to the task of encouraging bicycling in America. These beliefs are the root cause of why bicycling seems difficult, dangerous or impossible to most people. These beliefs have inhibited bicycling for decades.

These beliefs are a false construct that can be overcome by individual bicyclists. Even with all the imperfection of motorist behavior, the physical issues of land use, street design and other ills of our culture’s diversion into motor-centric transportation priorities, the individual can be empowered to thrive as a human-powered vehicle driver… right now. Not just the strong, brave, fearless….whatever. Anyone.

The green-shirted bicycle driver in the illustration at the top of the page is not unique by any physical characteristic, age or gender. That bicyclist is simply someone who has learned the same defensive driving skills taught to the drivers of another common narrow vehicle: the motorcycle. What’s less simple is that she had to overcome the baggage of the control mythology before she could learn the behaviors that allow her to have a successful and conflict-free experience. A future post in this series will discuss strategies for belief change.

The reward for the bicyclist is tremendous: empowerment for unlimited travel. But the reward for those of us wanting to encourage bicycling is also significant. This bicyclist tells stories, too. She tells stories about all the places she goes on her bike, how much better she feels when she arrives at a destination, how easy and rewarding it is to use a bike for transportation and how courteous her fellow road users are. She’s positively connected to her community. Her enthusiasm is infectious. It inspires her friends to dust off their bikes and try a trip to the park or the store, too. If they implement her style of riding, they, too, will be empowered by success. New positive stories will begin to edge out the old negative ones.

The reward for the bicyclist is tremendous: empowerment for unlimited travel. But the reward for those of us wanting to encourage bicycling is also significant. This bicyclist tells stories, too. She tells stories about all the places she goes on her bike, how much better she feels when she arrives at a destination, how easy and rewarding it is to use a bike for transportation and how courteous her fellow road users are. She’s positively connected to her community. Her enthusiasm is infectious. It inspires her friends to dust off their bikes and try a trip to the park or the store, too. If they implement her style of riding, they, too, will be empowered by success. New positive stories will begin to edge out the old negative ones.

The Stories of the Successful Bicyclist

I’m a first class citizen.

I’m in control of my safety.

Most motorists are safe and courteous.

Bicycling is safe, easy and a great way to connect with the community. I don’t need special infrastructure, but there are some ways better infrastructure could enhance my travels.

Imagine a community where this is the dominant story. At I Am Traffic, we believe we can make it so. But first, there are some common advocacy strategies we need to reexamine. That will be the topic of part two.