Washington, DC, USA is a planned city, with a north-south and east-west street grid, overlaid with a number of diagonal avenues. These add to connectivity and offer vistas of important landmarks. In the horse-and-buggy era, when the street plan was laid out, there was little concern for any resulting complication in traffic movements.

New Hampshire Avenue is one of the diagonal avenues, and its intersection with 16th Street and U Street is, as you might surmise, a 6-way intersection.

The image below, from Google Maps, gives an overhead view of the intersection.

U street (east-west) and 16th Street (north-south) are both major arterial streets. New Hampshire Avenue runs between northeast and southwest, and is less heavily traveled. Decades ago, New Hampshire Avenue was made one-way away from the intersection for one block in both directions. That way, there would be no need for traffic on 16th Street or U Street to wait for entering traffic from New Hampshire Avenue.

The interruption at 16th Street and U street improved cycling conditions along much of New Hampshire Avenue, diverting through motor traffic to other streets. Cyclists liked to ride New Hampshire Avenue. They rode the last block before the intersection opposite the one-way signs, or on the sidewalk, and crossed the intersection in the pedestrian crosswalks.

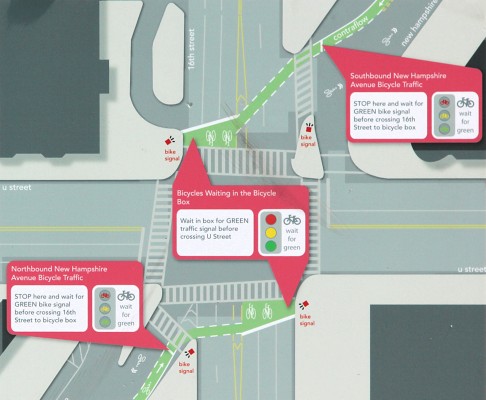

The intersection was reconfigured in 2010 with “bike boxes”—bicycle waiting areas, ahead of where motorists wait. In other writings, I’ve given details about “bike boxes”.

Special traffic signals and contraflow bike lanes also were installed, in an attempt to regularize and legalize bicycle travel through the intersection. The illustration below is from a sign which the Washington, DC Department of Transportation posted at the intersection. The sign describes how the intersection is intended to work. You may click on the image to enlarge it so you can read the instructions.

The bike boxes at this intersection are a variation on the “cross-street bike box” — as I have called it, or the “two-stage turn waiting area” as it is sometimes called. It facilitates a “box turn” — a left turn in two steps: going straight ahead, stopping a the far right corner — then turning the bicycle to the left and proceeding when the traffic signal changes. The two-step left-turn usually involves more delay than a left turn from the normal roadway position, but it doesn’t inherently violate any of the principles of traffic movement. Timid or inexperienced cyclists may prefer a two-step left turn. It can work for any cyclist at an intersection where normal left-turn movements are prohibited, or if an opportunity to merge does not arise.

When I first saw the plans for this intersection, I regarded them positively. I even wrote about this and published my comments. As I already said, a cross-street bike box violates none of the fundamental rules of traffic flow.

But , there is a saying:

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. But, in practice, there is.”

– Yogi Berra or Jan L. A. van de Snepscheut or maybe Albert Einstein

If I couldn’t laugh, I think I’d weep.

So, what’s the problem here?

In an ordinary four-way intersection, a cyclist can execute a two-step left turn using the same traffic-signal phases as other traffic. The cyclist will get a green light for the first step, wait on the far right corner and then get the green for the second step along with other traffic.

By introducing traffic — bicycle traffic — entering from New Hampshire Avenue, the DC Department of Transportation introduced the need for traffic signal phases which it had been avoiding. For this reason, the bike boxes here are not quite the usual cross-street bike boxes.

In May, 2011, I was one of several cycling advocates who converged on Washington, DC to examine cycling conditions. We discovered that theory and practice diverged widely at this intersection. Cyclists were not using it according to plan. Instead, they were using it as shown in the video here. This is an HD video and is best viewed full-screen, by clicking on the “vimeo” link.

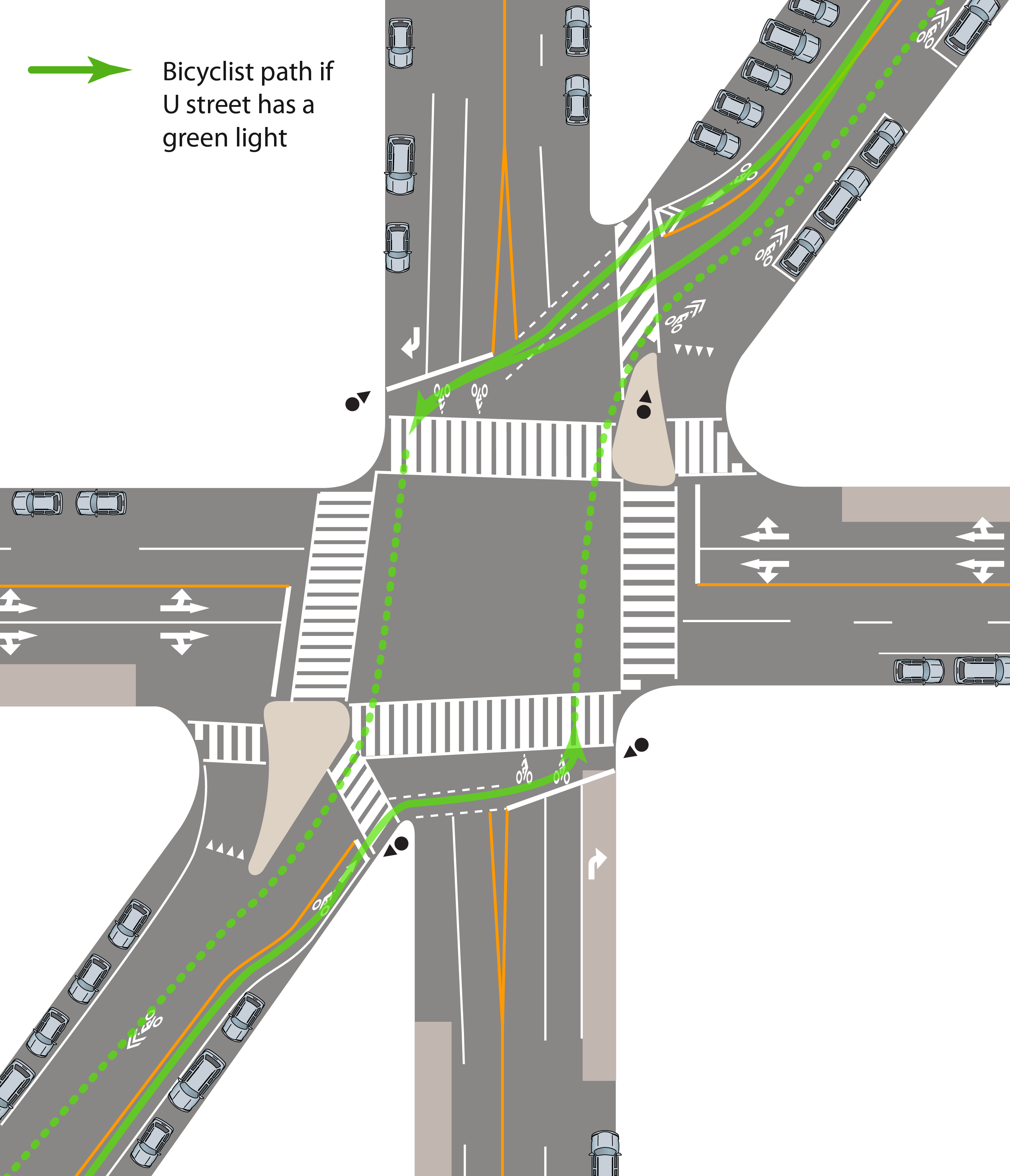

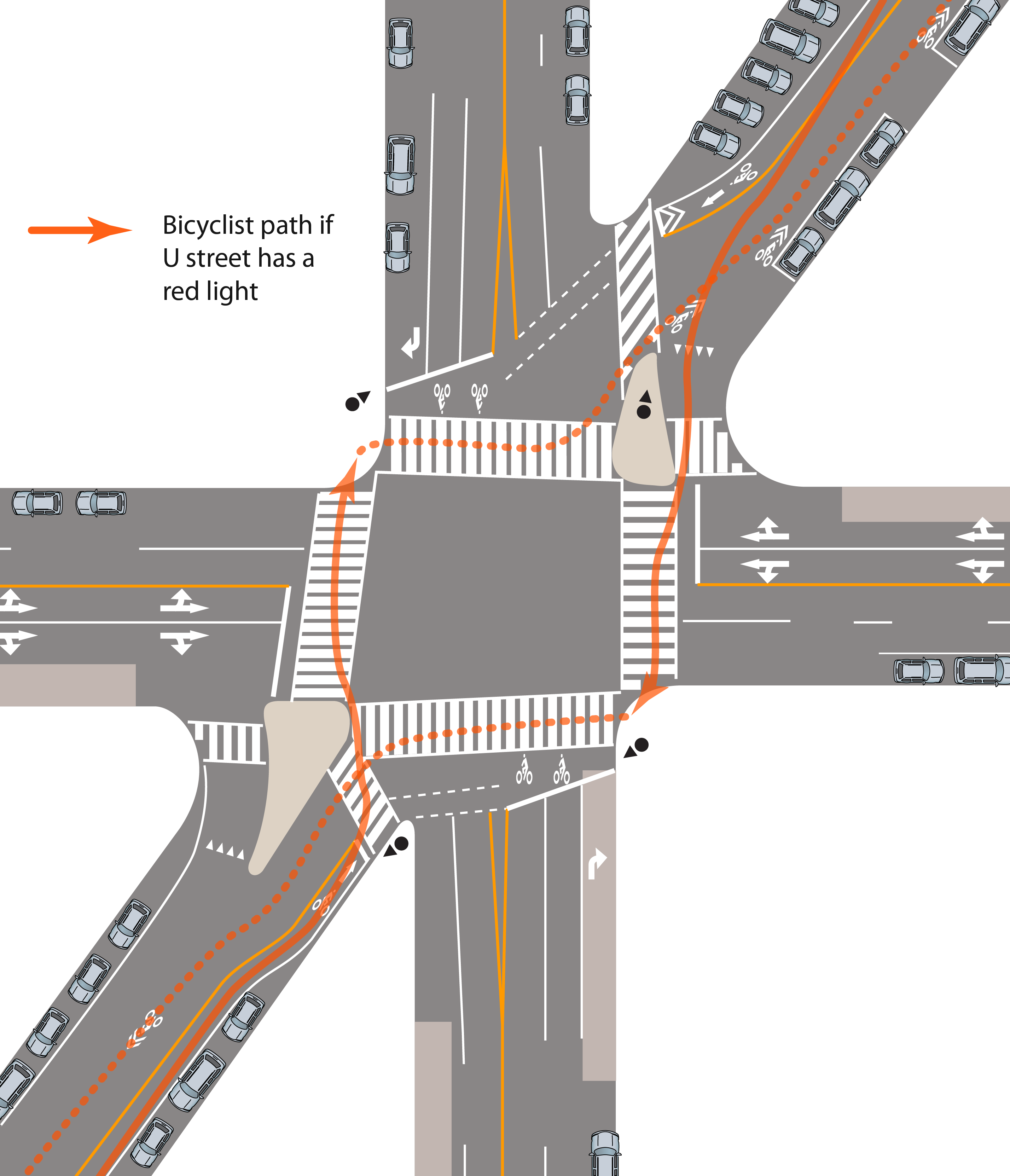

Keri Caffrey’s illustrations below show cyclists’ preferred lines of travel.

When U street (right to left in the illustration) has the green light, cyclists cross 16th street on the concurrent pedestrian signal phase, as shown by the solid green lines. Note that this does not mean that the cyclists have the green light with the special bicycle signal. The cyclists are in conflict with right-turning traffic from U Street. As the cyclists are not stepping directly off the corner like the pedestrians, and travel faster, motorists have a harder time seeing and yielding to the cyclists.

On reaching the far corner, the cyclists turn their bicycles left. As shown in the video, most wait in the crosswalk rather than in the designated bicycle waiting area. When the light changes, the cyclists proceed across U Street and bear right onto New Hampshire Avenue, as shown by the dotted green lines.

When U Street has the red light, cyclists travel around the intersection clockwise. They start by riding opposite traffic, then cross U street from right to left in the near-side crosswalk as shown by the orange arrows in the illustration below. The cyclists wait on the far left corner, then cross 16th street and continue on New Hampshire Avenue as shown by the dotted orange lines.

The video below shows three expedition participants riding through the intersection on the designated route, and obeying all the signs, signals and markings the best we could. Bear in mind that I have edited out most waiting for the special bicycle signal. Like the other video, this is an HD video and is best viewed full-screen, by clicking on the “vimeo” link.

vimeo.com/video/636810333

Why doesn’t everyone ride like us?

Why do few cyclists, other than our expedition participants, obey the special traffic signals and follow the designated route? There are several reasons:

- Before the intersection was reconfigured, cyclists developed the habit of crossing it along with pedestrians. A habit is harder to break when the proposed new behavior doesn’t offer an advantage.

- The special signal is supposed to be triggered automatically when cyclists are waiting to cross. Triggering is unreliable.

- The special signal is green for only 6 seconds of a 90-second signal cycle, and yellow for another 4 seconds. For most of the remaining 80 seconds, one or the other crosswalk is in the walk phase, and cyclists can get a start across the intersection along with pedestrians. The temptation is hard to resist.

- The designated space to wait for the special signal on New Hampshire Avenue is very tight, delimited by a barrier on one side and a curb on the other. There is only room for three or four cyclists to start on the green or yellow phase of the special bicycle signal.

- Extended yellow signals for cyclists are a well-known concept, yet the yellow signal for cyclists is not long enough to allow a decision whether to stop, or to cross 16th Street.

- 16th Street gets the green light only 2 seconds after the special bicycle signal turns red. Motorists behind cyclists in the bike boxes expect to be able to proceed on the green light. More than three or four cyclists will “accordion” in a bike box, when the first ones stop but the later ones do not have time to stop.

- Motorists regularly encroach into the bike boxes. Some motorists harass cyclists with horn blasts and close passes.

- The bike boxes are very small. There is hardly room for one cyclist to turn and wait — not to speak of several cyclists at once. This, and the encroachment problem, account for cyclists’ waiting in the crosswalk.

What lessons does this hold?

There are some design issues:

- Attempting to accommodate two new directions of travel traffic with minimal impact on the previous four-way traffic results in cramped space and extremely short signal phases for the two new directions of travel.

- The bike boxes at this six-way intersection differ from cross-street bike boxes at a four-way intersections, in requiring a separate signal phase.

- That results in delay and unwillingness to use the installation as intended, but it also imposes a severe capacity limitation. The special installation can never accommodate more than a low volume of bicycle traffic.

- Cross-street bike boxes at a four-way intersection are between the crosswalks and the roadway. Because the cyclists come from different directions at this six-way intersection, the bike boxes are behind the crosswalks.

- Because the bike boxes are behind the crosswalks and are small — also because of motorist encroachment and the convenience of starting closer to the intersection — cyclists who more-or-less follow the designated route (going around the intersection counterclockwise), wait in the crosswalks, partially or entirely blocking them.

There are also behavioral issues:

- Clearly, Washington, DC motorists are not accustomed to the bike box concept. The type of bike box used here — unlike the inline bike box — does not require X-ray vision or even unusual attention of motorists to avoid colliding with cyclists, yet motorists often encroach into the bike boxes, in most cases probably unknowingly or carelessly rather than maliciously.

- Some motorists also have an attitude problem, manifesting itself in the horn blasts and close buzz passes.

- Some cyclists operate carelessly or obliviously. This is especially the case with those who go around the intersection clockwise. The first stage of this route necessarily requires crossing New Hampshire Avenue, often followed by crossing U street at speed from right to left before the intersection –the most hazardous way for a cyclist to enter an intersection. .

- There is widespread illegal parking, especially by truckers, who often have no practical alternative. Illegal parking is common in the contraflow bike lanes leading to the New Hampshire Avenue/16th Street/U Street intersection. Illegal parking belies the presumption that cyclists can operate simply by following painted lines.

There are larger political and planning issues:

- If a special bicycle accommodation isn’t given the space or signal-phase time needed to make it practical or safe, is it worth the trouble to build at all?

- Should bicycling advocates be praising a city government for an installation which, in practice, simply doesn’t do what it is supposed to do?

- What can be said about a city government with a photostream that posts photos showing:

- a cyclist waiting in the crosswalk while the bicycle waiting area is open for use

- a cyclist waiting in the crosswalk while a city bus encroaches into the bicycle waiting area

- an illegally double-parked truck

- a promotional sign showing a bike box with ample space, and cyclists waiting for a light which has been red long enough to allow them to stop, contrary to reality?

- Should cyclists be expected to wait longer to use a special accommodation than to take an undesignated and mostly legal route across the intersection?

- What happens at this intersection if bicycle traffic volume increases?

- Can the long-term goal of improved bicycling conditions citywide be achieved through construction of installations that, in practice, don’t do what they are supposed to do? What is the political calculus here? Do we have to look forward to tearing all this down and starting over, like with the public housing projects of the 1950s?

- Might a larger scope of planning be looking at alternate routes, or a bolder solution (for example, a grade separation? Yes, they’re expensive, but Washington, DC has numerous grade separations on major streets — many times more expensive. This and following photos on the DC Department of Transportation photostream (click left on “newer”) show what kind of effort and expense went into those.

There are peripheral issues:

- I rate contraflow bike lanes on whether they meet the same safety standards as other lanes. The one north of U street: OK — the back-in angle parking avoids sight-line issues. The one south of U Street: not OK because it is in the door zone, and with wrong-way parking, motorists pulling out of parking spaces can’t see cyclists in their rear-view mirrors and many can’t see the cyclists at all.

- Shared-lane markings for cyclists proceeding away from the intersection are painted in the door zone of parked cars.

Links

The most recent post about this intersection on my own blog — includes links to earlier posts

A collection of all the videos of this intersection from the May, 2011 expedition

DC DOT photostream of the installation (first of several photos. Click on “newer” to see the others.)

DC DOT evaluation of bicycle facilities showing an increase in crashes following this installation

Washington Post article with quote from DC’s DOT director

GreaterGreaterWashington blog post about the intersection, with extensive comments.

BikeArlington forum, comments that the traffic signal doesn’t trigger reliably

The Washcycle post about the project