Successful bicyclist behavior is driven by knowledge of common crash types and the behaviors needed to successfully avoid those crash types. Bicyclist behavior comes in a spectrum with three main behaviors, and in this article we aim to briefly describe the spectrum and show how those behaviors fare in common crossing conflict crash scenarios with diagrams and supportive video.

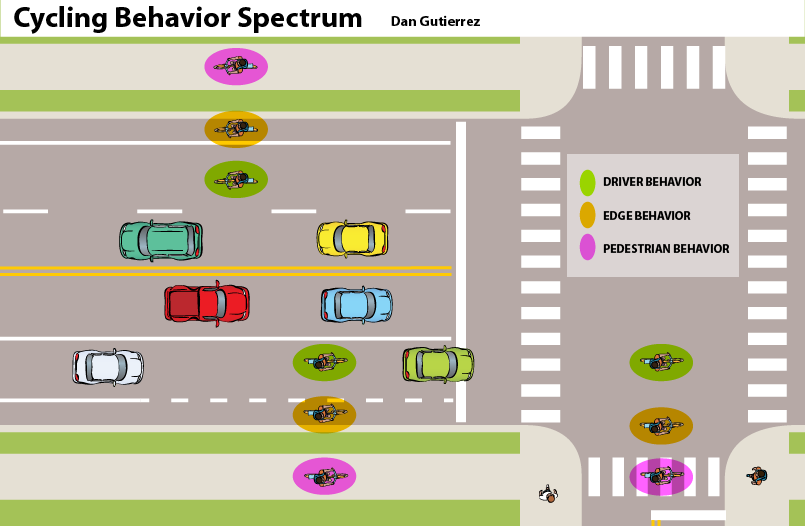

There are three types of bicyclist behavior:

Pedestrian behavior

Avoiding the roadway by using paths, sidewalks/crosswalks, often against traffic flow

Edge behavior

Operating at the roadway edge or close to parked cars, includes shoulder and edge bike lane use

Driver behavior

Following the rules of the road by using roadway through lanes and turn lanes as an equal driver

The behavior descriptions above meant to describe behavior at a particular place and time, not people, since a cyclist for example who prefers to engage in driver behavior on normal roads, may be required by law to engage in edge behavior in an edge bike lane. When operating on a crowded shared use path that is away from roads, with high pedestrian volumes, that same cyclist who would prefer driver behavior, may have no choice but to use ped behavior to avoid crashes. So it is not uncommon for cyclists to engage in multiple behaviors on a single trip.

This is why we don’t talk of edge cyclists, though a cyclist may be edge riding on a particular facility, and similar for driver and ped behavior. It is also important to understand that unlike edge and ped behavior, driver behavior is a learned behavior that must be taught; it is not innate. So just because a bicyclist who may at present prefer the more common edge or ped behaviors, does not mean that they will never learn driver skills and/or engage in driver behavior, so we recognize that behaviors are not in general fixed and can change over time and exposure to skills training.

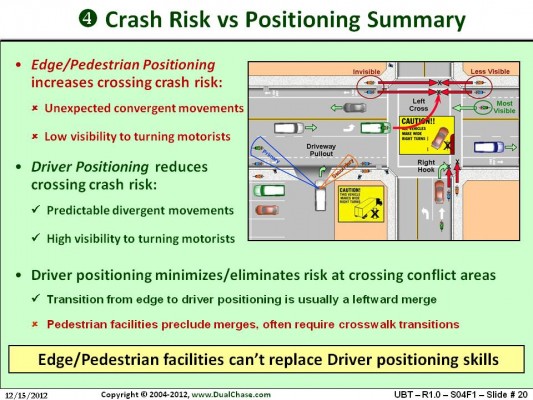

The value in identifying behavior, instead of cyclists themselves, is its descriptive power in identifying how behavior influences crash likelihood and why some behaviors are more successful than others in an urban environment with driveways and intersections, the places where most cycling crashes occur. The most common types of crashes are referred to as crossing crashes, where the paths of a turning motorist at a driveway or intersection and a straight through cyclist can potentially cross, creating conflicts and crashes. Because of this, we often refer to driveways and intersections as crossing conflict areas.

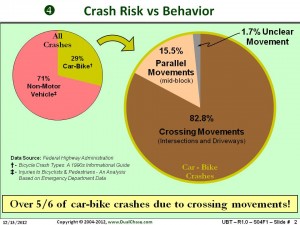

The pie chart couplet (right) shows that even though car-bike crashes comprise the minority of cases where bicyclists hit the ground, when expanded to a full pie (at the right side), the crossing crashes comprise about 5/6 of the total number of crashes. In examining these crossing crash types, we can learn a great deal about behavior and the facilities and laws that enable or restrict behaviors, influence how successful cyclists will be at negotiating urban roads.

The pie chart couplet (right) shows that even though car-bike crashes comprise the minority of cases where bicyclists hit the ground, when expanded to a full pie (at the right side), the crossing crashes comprise about 5/6 of the total number of crashes. In examining these crossing crash types, we can learn a great deal about behavior and the facilities and laws that enable or restrict behaviors, influence how successful cyclists will be at negotiating urban roads.

Crossing Conflict Types

Let’s examine the three main crossing conflict types and the effect of bicyclist behavior. The three types are pullout, left cross and right hook. These conflicts occur at driveways and intersections. We’ll examine each individually.

Pullout

(shown in the diagram at a driveway)

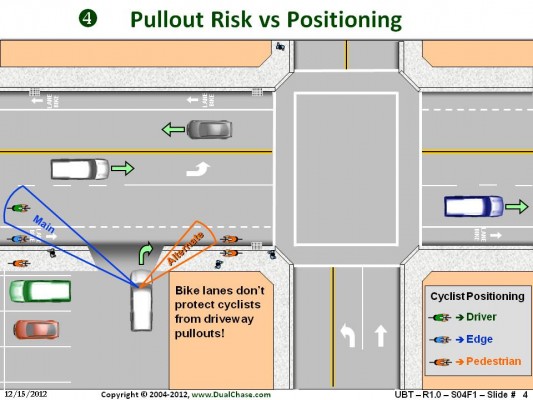

A pullout occurs when a motorist leaves a driveway or turns right at an intersection and approaches a cyclist from the right side, perpendicular to the cyclist’s through line of travel, resulting in a side impact to the cyclist, or causing the cyclist to hit the side or rear of the vehicle if it turns sooner in front of the cyclist.

Look at the driver of the silver SUV approaching the driveway, prior to making a right turn into the street. The driver is mainly looking to the left for road traffic, such as cars and trucks, so a bicyclist using driver behavior is more easily seen (visibility) by the SUV driver because they are operating where drivers pulling out of driveways are expecting approaching traffic to be located in the roadway. In addition, that same bicyclist can see further down the driveway (vantage) and determine when a motorist is preparing to make a right turn. Visibility and vantage go hand in hand when a bicyclists is further leftward in the roadway.

A bicyclist using edge behavior is not where motorists expect cyclists to be, and may be visually shielded by fixed sight line obstructions such as foliage, and street furniture, or even dynamic obstructions such as peds. Thus a motorist may not see a bicyclist at the edge and turn in front of them. An even more difficult dynamic occurs when bicyclists are on the sidewalk engaging in ped behavior. Here they not where motorists are expecting them to be (in the road), and are even more susceptible to visual screening by fixed and dynamic obstructions, so they have minimal visibility and vantage; the opposite of the driver behavior case.

Now we need to consider that motorists about to exit a driveway or turn at intersections also look to their right. They use this alternate scan to look for slow moving, about 2-3 mph peds on the sidewalk. They are not expecting or looking for much faster bicyclists facing traffic on the sidewalk, or the illegal bicyclists riding facing traffic at the road edge. So these “backwards” edge and ped behaviors have even poorer visibility and vantage than their normal flow counterparts. Notice also that there is no “reversed” driver behavior, driver behavior skills classes teach cyclist to never operate this way.

It should come as no surprise that bicyclists are more frequently injured by pullouts when operating on the sidewalk or at the road edge. These behaviors are less successful than driver behavior in negotiating driveways and intersection pullouts.

In the tabs below are video clips showing pullout scenarios.

[tabs slidertype=”top tabs”] [tabcontainer] [tabtext]Video Example 1[/tabtext] [tabtext]Video Example 2[/tabtext] [tabtext]Video Example 3[/tabtext] [/tabcontainer] [tabcontent] [tab]

An edge rider passes stopped traffic on the right to pass a motorist about to leave a driveway.

[/tab] [tab]

This clip shows a driveway pullout hazard from a blind underground driveway. In this video it was clear that poor vantage and visibility from ped behavior can increase bicyclist exposure to pullouts.[/tab] [tab]

In this clip, we have one more example of a bicyclist trying to ride at normal traffic speed on the sidewalk to pass slower traffic in the road, and still dodge cars waiting to pull out as well as street furniture like a newspaper box.[/tab] [/tabcontent] [/tabs]

Left Cross

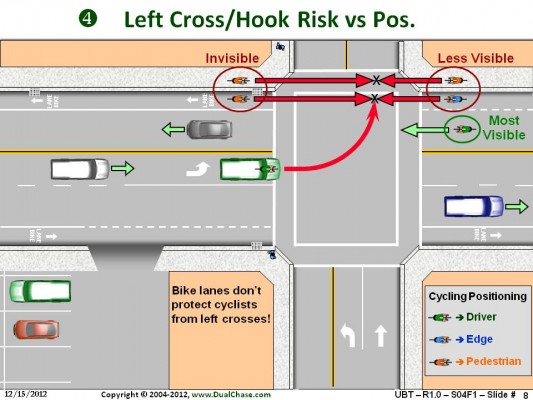

Happens where a cyclist is making a through movement and an oppositely directed motorist makes a left turn in front of and across the bicyclists’ line of travel.

Again we see that a motorist waiting to make a left turn at an uncontrolled crossing, has a clear view of a bicyclist using driver behavior, and a progressively more difficult time seeing bicyclists using edge or ped behavior in the direction of traffic, since they can be lost in visual chatter at the road edge, including street furniture, foliage or even peds. Here again we find that driver behavior gives the best visibility and vantage to cyclists approaching a crossing conflict area. For cyclist on the sidewalk, or even in the road, they are approaching from a direction behind the left turning motorist, and in their blind spot, so neither the bicyclist nor the motorist in such a “left hook” (the mirror image of the “right hook”, the next crash we cover) crash see each other until just before contact since the visibility and vantage are both very poor.

The tabs below contain video examples of left cross and left hook conflicts.

[tabs slidertype=”top tabs”] [tabcontainer] [tabtext]Video Example 1[/tabtext] [tabtext]Video Example 2[/tabtext] [tabtext]Video Example 3[/tabtext] [/tabcontainer] [tabcontent] [tab]

Even a left turning bicyclist using driver behavior may left cross another bicyclist who is engaging in ped behavior on the sidewalk, since the visibility of the sidewalk bicyclist approaching the crosswalk is very poor.[/tab] [tab]

And here is another case where a fit female cyclist is screened by stopped traffic in the travel lanes, and because of this neither she nor the motorist turning left could see each other approaching. While the motorist is legally at fault for not yielding, the cyclist could not see far enough ahead at her speed to stop in case motorist did make an ill-advised turn across her path.

In the above video the lesson is that facilities that enforce edge behavior often create poor visibility/vantage crossing conflicts, compared to encouraging driver behavior.[/tab] [tab]

And finally we show a video of a cyclist riding facing traffic to demonstrate the difficulties when cyclist ride facing traffic, on either the sidewalk or in the roadway.[/tab] [/tabcontent] [/tabs]

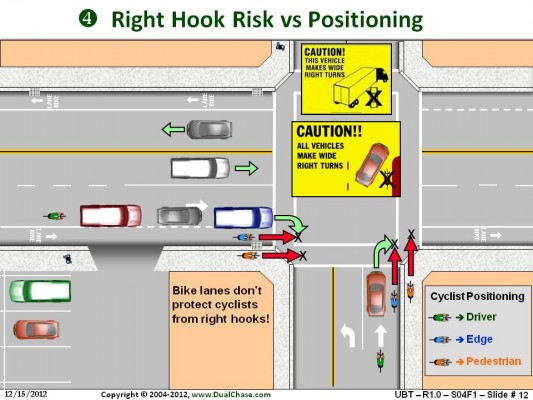

Right Hook

The last crossing crash type we will examine in terms of behavior is the right hook, which is the most frequent cause of car-bike crashes, and leads to many bicyclist fatalities.

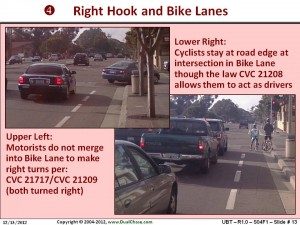

The classic right hook crash comes in two varieties; a bicyclist riding near the edge (edge behavior) is passed close to the intersection by a motorist traveling in the same direction, who then proceeds to turn right in front of the cyclist, cutting her off and causing a crash. In the other the bicyclist approaches a motorist stopped at the intersection waiting to turn right and tries to pass on the right (edge behavior again) as the motorist starts their turn. In the first case the motorist is at fault for turning in front of another moving vehicle, in the second, the cyclist is at fault for passing a right turning driver on the right, though drivers often “help” the cyclist make the mistake by not driving close enough to the edge to preclude passing by cyclists on the right. These scenarios can be seen in the lower right of the image below:

In a similar way, a bicyclist on the sidewalk can be hooked by a motorist, or ride into the path of a right turning motorist. In contrast a bicyclist engaging in driver behavior, by riding in the center of the travel lane, discourages motorists from passing on the intersection approach, thus precluding the first type of right hook where the motorist passes close to the intersection. Driver behavior also avoids the second type by allowing the cyclist to either wait behind the motorist stopped to make a turn, or to pass the stopped motorist on the left, thus successfully staying away from the crossing conflict. Engaging in edge or ped behavior is much like driving a motor vehicle, such as a sedan, inside the turn of a large truck, which is why the yellow sticker at the top is often placed on the rear of large trucks. The same issue, scaled down, is also true for bicyclists engaging in edge behavior, riding inside the turn of a much larger motor vehicle, so we ask cyclists to imagine that the lower sticker was on the back of every car.

Look to the left side of the diagram, which is the case for bike lanes. Bicyclists often edge ride and stay in the bike lane on the intersection or driveway approach, even though the law allows them to exit bike lanes to avoid crossing conflicts by using the more successful driver behavior, and right turning motorists often stay to the left of the bike lane instead of merging into it as is required by law (bike lane is part of the roadway and right turns are to be mad from as close as practicable to the curb or edge of the roadway). Taken together, these behaviors tend to manufacture crossing conflicts where motorists are allowed to make right turns on roads with typical minimum standard bike lanes. The image to the right is a California example photo showing that motorists and bicyclists often cooperate to create intersection conflicts when bike lanes are present.

Look to the left side of the diagram, which is the case for bike lanes. Bicyclists often edge ride and stay in the bike lane on the intersection or driveway approach, even though the law allows them to exit bike lanes to avoid crossing conflicts by using the more successful driver behavior, and right turning motorists often stay to the left of the bike lane instead of merging into it as is required by law (bike lane is part of the roadway and right turns are to be mad from as close as practicable to the curb or edge of the roadway). Taken together, these behaviors tend to manufacture crossing conflicts where motorists are allowed to make right turns on roads with typical minimum standard bike lanes. The image to the right is a California example photo showing that motorists and bicyclists often cooperate to create intersection conflicts when bike lanes are present.

And now we give some video examples in the tabs below.

[tabs slidertype=”top tabs”] [tabcontainer] [tabtext]Video Example 1[/tabtext] [tabtext]Video Example 2[/tabtext] [/tabcontainer] [tabcontent] [tab]

This video shows an edge behaving bicyclist passing on the right in a faded bike lane and luckily the motorists, who didn’t merge into the bike lane to prevent such right side passing, didn’t turn into her. The bicyclists using driver behavior had nothing to fear, since they were not in the conflict zone.[/tab] [tab]

This video shows a ped behaving bicyclist entering the crosswalk in front of a driver turning right. The bicyclist didn’t look to the left, where the threat originated. Shows that ped behavior can be problematic at intersections, especially when the threats are ignored.

[/tab] [/tabcontent] [/tabs]

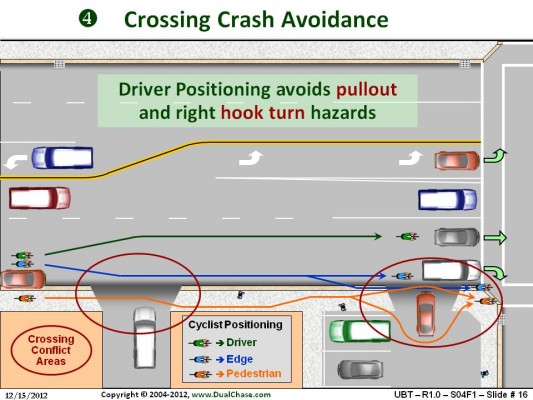

Avoiding Conflicts: Driver Behavior

Next we show how driver behavior allows bicyclists to successfully avoid crossing conflicts.

The tabs below show video examples of conflict-avoidance through driver behavior.

[tabs slidertype=”top tabs”] [tabcontainer] [tabtext]Video Example 1[/tabtext] [tabtext]Video Example 2[/tabtext] [tabtext]Video Example 3[/tabtext] [/tabcontainer] [tabcontent] [tab]

In this example, the bicyclists are approaching a complicated intersection with preceding driveways, and transition from lane sharing (more like edge behavior) to lane control (driver behavior) near the intersection to discourage pullouts and right hook turns:[/tab] [tab]

Here we show how a merge from edge to driver behavior avoids a pullout conflict.[/tab] [tab]

Here we compare a manufactured engineering conflict of combined edge/ped behavior versus driver behavior in side-by-side fashion.

In the right side video, the designers try to force the cyclists to engage in ped behavior, and this puts them at a severe disadvantage at the uncontrolled ped crossing (crosswalk). Compare how long it took for the cyclists on the right to reach the same place the cyclists on the left reached by using the more successful driver behavior.[/tab] [/tabcontent] [/tabs]

In summary bicyclists are more successful when they understand driver behavior, since it is often the only successful way to negotiate intersections and driveways, by ensuring that they are seen by traffic and can see traffic (visibility/vantage). Special facilities that force ped behavior prevent the types of leftward merges that allow bicyclists to transition from edge to driver behavior on approaches to crossing conflict areas.

In our next article we will describe how road and bikeway facilities interplay with the behaviors and crossing conflicts, as well as some of the parallel movement hazards. We will show how engineering designs and traffic controls can support successful behaviors, and not discourage or prevent bicyclists from employing them.

For the less then 1/6 of car-bike crashes involving parallel movements (most likely motorist rear-ending or side-swiping cyclist) in this or other studies, do we have any data about where the cyclists were positioned on the roadway? Edge or driver behavior (lane control)?

We almost never get control vs edge behavior breakdowns in crash stats for crashes in the roadway. What is usually captured is whether the cyclist was operating with or facing traffic, and whether on the sidewalk or on the road.

Why do you say only driver behavior is learned, while edge and ped behaviors are innate? We emerge mewling from the womb knowing nothing about any of this. The latter two behaviors are indeed almost universally observed among cyclists who have not learned driver behavior, but that only means they were learned by means outside the scope of formal education. That informal miseducation (“my momma taught me” or “everybody does it” or “it’s just common sense”) brings the learning that is most difficult to displace.

Edge and ped behaviors are part of the culture, so one assimilates it from birth onward. Moreover, the taboo against driver behavior inhibits learning about it, since most presume it is not viable.

You say that edge and ped behavior are “innate”, but that behavior is educated into kids. Kids naturally want to play anywhere and everywhere including in the roadways. But we adults scold them that they cannot play in the roadway and that they must fear cars and trucks and stay to the edge or out of the roadway completely. Over and over we grind this into their heads. Is in no wonder they have a hard time abandoning this later in life to become a bicycle driver?

I’ve examined detailed police reports for about a dozen overtaking-type crashes in the Triangle area of NC over the last 10 years. All of the ones I’ve read report the cyclist to have been riding at the edge of a narrow lane or on a narrow shoulder. In most of the daytime cases where the driver was found, the driver said that they saw the cyclist but assumed that they had room to pass without changing lanes, or that they were unable to change lanes but decided to risk the close pass rather than slowing down. Other cases were cyclists riding at night without lights, or drunk motorists, or sideswipe hit-and-run.

I’ve also heard word-of-mouth reports of a couple of low speed rear-ending collisions with cyclists in my area. In each case the driver was distracted and not looking in front of them when traffic started moving, and the accelerated into the cyclist at low speed.

Innate? learned? I think that edge and pedestrian behavior are mostly a response to misunderstanding of risk, or to fear. Two examples: myself, moving to Boston in 1971. Nobody had taught me what to do, but I simply assumed that the risk of a rear-end collision was much higher than it is. I knew that I was riding into dangerous potential blind conflicts by edge cycling, but until I read john Forester’s book Effective cycling in 1977, I assumed that this was the lesser of two evils. My other example is Marty, an active member of the Charles River Wheelmen who was mildly retarded and was raised in a special state school. He was an exemplary cyclist and also a good driver. With his unusual upbringing, he had not learned fear.

One major omission from this material and the comments is the vital importance of having a rear-view mirror attached to sunglasses or the handlebars. That way the cyclist continuously knows what vehicles are approaching from behind him so that he/she can anticipate potential problems. I am surprised that few cyclists use this essential piece of apparatus, it will alert cyclists of potential problems well before they occur. Additionally, it is often not possible to ride in a travel lane rather than the edge of the road because cars are traveling much faster than cyclists are able to ride, so edge riding is far more often necessary unless one is in the slower car traffic of an inner city.

Scott, is this the kind of high-speed road where you think edge riding is necessary?

https://vimeo.com/album/1881848/video/15723369

Scott Smith, This material was developed to show the three basic behaviors, and their relative susceptibility to crossing crashes. It was not designed to teach cycling skills like mirror use, or the more general topic of scanning and situational awareness, so what you describe is not an omission, it was deliberate.

Additionally, I couldn’t disagree more with your assertion that “it is often not possible to ride in a travel lane rather than the edge of the road because cars are traveling much faster than cyclists are able to ride, so edge riding is far more often necessary unless one is in the slower car traffic of an inner city.”

Rather than use words, please watch these videos to see more of cyclists (using mirrors to scan BTW, so as to keep the helmets facing forward to make good video) controlling lanes on roads with higher speeds and more complex traffic interactions:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rU4nKKq02BU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F1C3qqhW6Aw

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6W0twza9B7o

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WZkhgXaR064

There are even more videos on the I Am Traffic/Cyclist Lorax channel on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/user/CyclistLorax/videos?sort=p&view=0&flow=grid

And also check out the Commute Orlando channel:

http://www.youtube.com/user/CommuteOrlando/videos?sort=p&view=0&flow=grid

I think videos demonstrating competent and knowledgeable cyclist behavior on the road is an invaluable tool that the instructor should use to supplement hands-on instruction.

I urge my students and others to view the same material referenced by Dan Gutierrez above, such as http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rU4nKKq02BU which is the first one I like to recommend.

However, it must be recognized that only practical instruction will convert the skeptic into a confident cyclist. That starts in a parking lot to introduce and practice bike handling and crash avoidance techniques, followed by solidly-based on-road instruction, as taught in Cycling Savvy.

I can also confirm what John Allen wrote above about an understanding of safe on-road cycling being the result of reading John Forester’s Effective Cycling book. In my case, that was the 1984 edition. Before that, I was a confirmed and strident supporter of segregated off-road cycletracks, as they were called in England.

Scott, no law says you have to ride the same speed as the cars to use a narrow travel lane, or to put it another way, that they must be able to pass you at all times. I’ve had success with the CyclingSavvy method called “control and release”, when you hold them behind you if it’s unsafe to pass, then indicate with a hand motion, head nod, and/or slight move to the right when you judge it’s safe. This is mostly necessary on narrow two lane roads, and it works. It’s not always pleasant, of course, but it makes riding on such roads possible if you need to, to get where you’re going. I’ve found motorists generally very willing to move over to give me enough passing clearance, if they have the room to. When they don’t is when you’ll get risky close passes if you don’t actively prevent it, and the narrowness of the lane gives you the legal right to do that. What’s more, it works.

As to a mirror, it’s a fine idea, but it’s not high on my list. Many knowledgeable cyclists I know use one, but I choose not to, purely for convenience. I tend to just break or lose them. I really don’t think you need to monitor behind you 100% of the time. When I feel the need to know who’s where behind me, I turn my head.

Dan, I hope you will be soon sharing yours and Brian’s designs for sharrows and bike lanes in the engineering section of this website. That is something I would like to refer people to when they ask my about special facilities for cyclists.

— Gary

I have got to say watching many of these videos has really helped me. To be more confident in controlling lanes. I used to be scared to control lanes for fear of getting hit from behind. I used to be also scared of the occasional irate motorists that would lay on their horns or yell crap from behind me. Until someone pointed out that if someone is honking or yelling at you, they are acknowledging that they see you. Which eliminates the most common defense used by hit and run drivers. “I didn’t see the cyclist in front of me” Kind of hard to beep at and yell at someone you can’t see.

Gary,

Bringing up sharrows and bike lanes is very timely for me in Ferguson, North St. Louis County, Missouri.

I just received an award from the Missouri Bicycle & Pedestrian Federation recognizing my efforts resulting in replacing “Far to the Right” language in Ferguson’s local ordinance with one containing the following language:

“Every person operating a bicycle or motorized bicycle at less than the posted speed or slower than the flow of traffic upon a street or highway may ride in the center of the right lane of travel or may ride to the right side of the roadway; such person may move into the left lane of travel only while in the process of making a left turn.”

Receiving recognition with me were Elizabeth Simons, Live Well Ferguson Program Manager, and Gerry Noll, a CSI and owner of the Ferguson Bicycle Shop.

I’m working with the city manager, John Shaw, who’s been very cooperative, on installing Bikes May Use Full Lane (BMUFL) signs on all major 4-lane roads, complemented by suitably spaced (400 yards) lane-centered sharrows. (There’s no on-street parking currently allowed.)

Elizabeth and Gerry are suggesting adding lane-centered sharrows on minor 2-lane collectors, not just 4-lane roads.

Would that be helpful or will it devalue their use on the main roads?

On minor 2-lane collectors (e.g. 11 ft. lanes) I practice control and release, controlling only when I consider it necessary, e.g. when approaching a blind bend, or a junction where experience has taught me I’m liable to being cut-off by right turning traffic if I share the lane.

Note: Last August the Ferguson Plan Commission gave its blessing to a Bike/Ped. Plan envisioning sharrows as a prelude to installing bike lanes and possibly even bike boxes on major roads. This was subsequently adopted by the full council.